Supercooling organs buys time for transplants

A new slow-cooling technique makes it possible to transplant a donated liver that's been outside the body for four days. Right now, the limits of human organ storage are about six to 12 hours, maybe up to 24 hours in some cases.

Not only would supercooling keep organs from spoiling, it would also widen the geographic range of donor organs intercontinentally. So far, the preservation technique has at least tripled the storage time of viable rat livers for transplanting into other rats. Because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already approved most of the method's chemical components for use in humans, Nature reports, clinical trials could begin just two years after it's tested in larger animals.

Developed by Harvard's Korkut Uygun and colleagues, the approach combines subzero, non-freezing -- or supercooled -- tissue preservation with extracorporeal machine perfusion, which delivers oxygen and nutrients to the tiny blood vessels in tissue while they're outside the body.

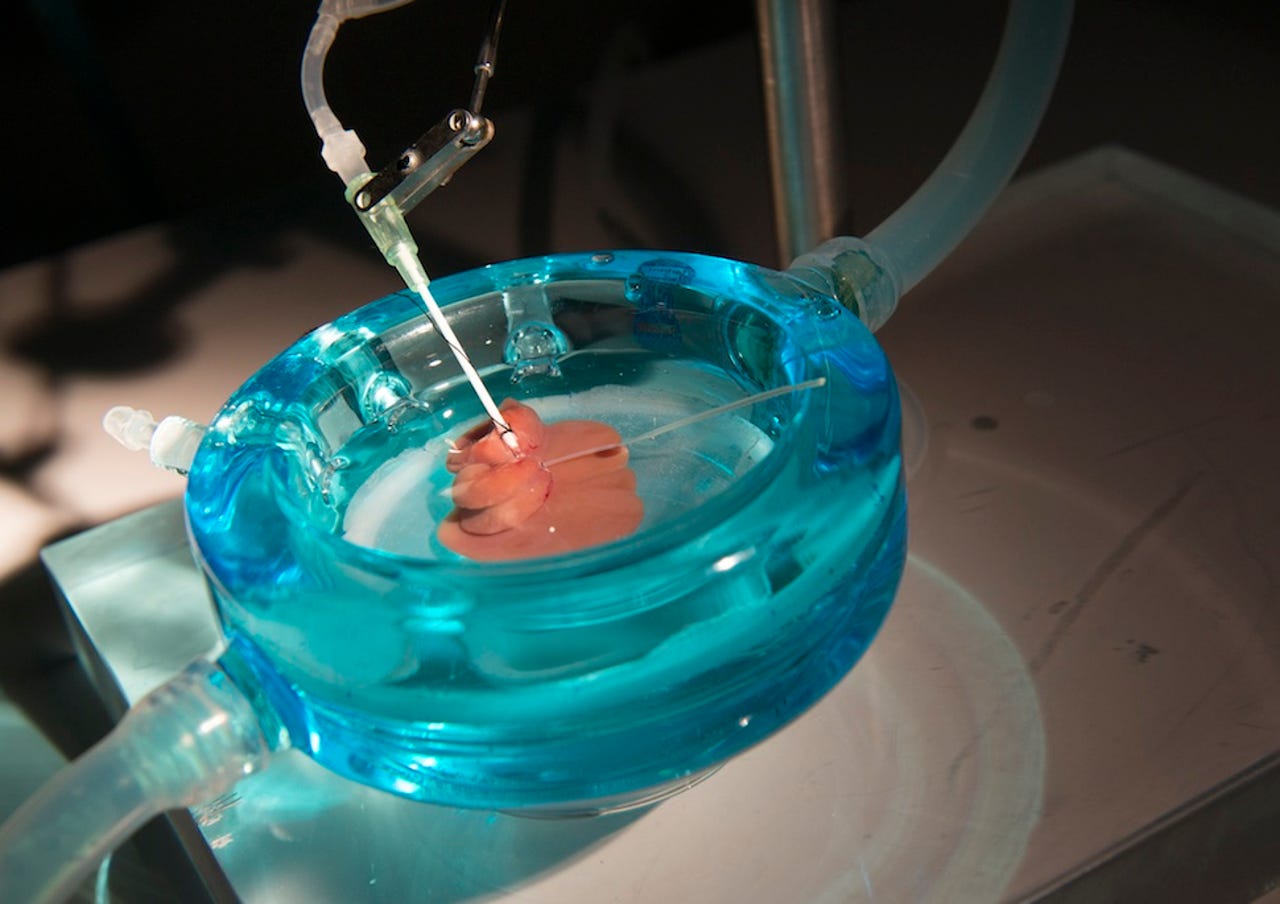

Here's how it works, according to a National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering press release. First, the liver is perfused with a solution in the pump system pictured to the right below. The blue color is caused by the "cryoprotectant" chemicals that act together as antifreeze that surrounds the components of the system and prevents ice from forming. This temperature regulating solution contains:

- A nontoxic, modified sugar compound called 3-OMG (3-O-methyl-D-glucose). Because 3-OMG can't be metabolized, it accumulates in the liver cells and acts as a protectant against the cold.

- Secondly, PEG-35kD (polyethylene glycol) protects cell membranes in particular. The active ingredient in antifreeze is ethylene glycol, and it works by lowering the freezing point of the solution, keeping it liquid even at subzero temps.

After this first round of perfusion, the livers are slowly cooled below freezing point to minus 6 degrees Celsius (21 degrees Fahrenheit), but without inducing freezing -- this supercools the organs for preservation. After storing the organs like this for a few days, the livers are perfused with the solution in the pump system again, to rewarm the organ and prepare it for transplantation.

In contrast, no livers were viable for three days using conventional methods that combine cold temps with chemical solutions developed in the 1980s. More than 120,000 patients are still on waitlists for organ transplants in the U.S. alone, and 17,000 of them are waiting for livers. The new technique could rescue organs that are marginally damaged (and usually discarded), creating thousands more donor options, New Scientist reports. It would also buy time to prepare organ recipients.

Uygun tells Nature that with a bit of tweaking, the method should scale up to larger organs, including human ones, and wouldn't be limited to livers. "All organs are fair game," he adds.

The work was published in Nature Medicine yesterday.

[NIH via Nature, New Scientist]

Images: Wally Reeves, Korkut Uygun, Martin Yarmush, Harvard University

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com