The bar for digital experience is rising in exponential times

Back in the early days of the Internet, many companies struggled initially with the imperative for creating Web sites. They tried to find motivation when the fuller industry implications of the new but clearly important new medium were still unclear. The same cycle also happened with subsequent evolutions of what's now increasingly called online digital experience, including the arrival of Web-based advertising, social networks, online communities, and mobile apps to name some of the more significant advances in recent years.

The pattern seems fairly consistent: Novel technologies emerge, which enable fundamentally new possibilities. Then companies try to figure out how to apply them to best benefit their businesses, often at first missing what makes the new technologies special. Instead, they employ them like they did previous advances.

Then a few stand-out exemplars -- usually from the startup world -- demonstrate the inherent advantages of the new technologies with a notable market proof point, typically a digital experience that has successfully drawn in and created value for millions of people in an important new way that is somehow better, cheaper, and/or easier. The resulting industry dissection and distilling of the lessons from these examples then seep back into the mainstream, though often more slowly than we'd like.

Pattern: Paving the Cowpath, Then Usage for Strengths

Thus the first Web sites looked like traditional brochures, digital ads were broadly blasted like newspaper ads instead of being narrowly targeted and algorithmically placed, social media was used by businesses as mostly a publishing medium rather than for more meaningful and productive engagement, and so on.

The good news is that in the large, the uniqueness and inherent strength of each new technology advance is steadily and slowly unlocked and then broadly learned. It almost always takes many years to do this however, often five to ten or more years, before an important new technology's uniquely significant aspects are well understood and broadly applied by the industry.

All would be still be relatively well if learning new technology was our only challenge. However, as influential thinkers like Ray Kurzweil have long posited, we would soon enter a world of exponential change driven by technology, and in particular, the power laws of computer networks. This is now the reality we live in.

Today, each new major technological advance in digital experience therefore comes more and more quickly. Consumer products, which can most easily take advantage of these ideas, are being adopted ever more and more quickly. This is a result of the almost complete lack of friction existing today in digital distribution, and am improved general understanding of the growth and adoption of digital experiences.

Examples of the kind of rapid shifts and fast growth that are possible abound: Tablets became mainstream in the shortest amount of time of any technology up to that point in 2012. Most recently, Pokemon GO was able to acquire its first 50 million users in just 19 days. On the business side of digital experience -- a more challenging space with additional barriers to user acquisition -- the growth stories of Slack or Dropbox have shown it's still possible to achieve very significant and viral growth.

The key insight here is this: Many of these new online services become substantial digital channels in their own right and to which companies often must respond, which has led to digital channel proliferation/fragmentation and what I recently dubbed as "The Engagement Paradox" in Brand Quarterly. Companies now have to be on Facebook (and most other major social networks), have a strategy of some kind for tablets, Internet of Things, Slack, and file sync and sharing, as well as hundreds, even thousands, of other engagement channels.

Most organizations simply don't have the resources to participate in these new channels, despite the benefits of doing so. Yet do it they must, as customer experience has become perhaps the top differentiating factor that separates the leaders and the laggards when it comes to corporate performance, according to a widely followed yearly report by Watermark Consulting.

The short version: Customer experience laggards underperform the S&P 500 significantly as a whole, while leaders outperform it by a good margin.

The implication is if you're not participating in a popular new digital channel, then your customer experience is missing entirely. You have no chance to engage or create value there. This also highlights a related issue: One's overall share of digital experience drops as new digital channels continue emerge and grow en masse. This is a real risk to many organizations as they fall behind, except for the minority that have figured out how to organize and scale better for exponential digital change.

To underscore this point, recent industry data from McKinsey shows there's no bell curve here: There are relatively few companies in the vanguard of digital maturity today, while the great majority are behind, and even regressing due to how fast technology is moving past them.

The Digital Experience Treadmill Speeds Up

While we now have some inkling at least of how we might better keep up with the drumbeat of digital progress, a whole raft of new incoming digital experience technologies, from Internet of Things to virtual and augmented reality, are inbound and demanding at least careful evaluation and planning, if not outright early experiments to build initial competency and organizational knowledge in these vital new areas.

It's important to point out as well that most of these digital experience advances are additive and very few truly replace what came before. So while e-mail and Web sites emerged in the early and mid-1990s, and certainly e-mail is getting very long in the tooth, it's still a valid and widely used channel for communication and engagement. This means all of the old digital experience capabilities must be maintained and used, until returns from them diminish sufficiently.

This has led to the outsourcing of digital channel handling and management to what are known as customer experience management (CEM) vendors, such as Adobe and Sitecore, which can theoretically cope with and handle new channels on the behalf of their customers, as new ones emerge.

However, given the early maturity phase of the the CEM industry, I'd argue that, for the moment, these platforms largely address only the largest and most well-known channels of the day. This is a scale challenge similar to the unified communications industry, which also isn't keeping up very well with recent advances in digital experience and engagement. So, I find that CEM is promising, but far from a panacea.

Today's Top Digital Experience Channels

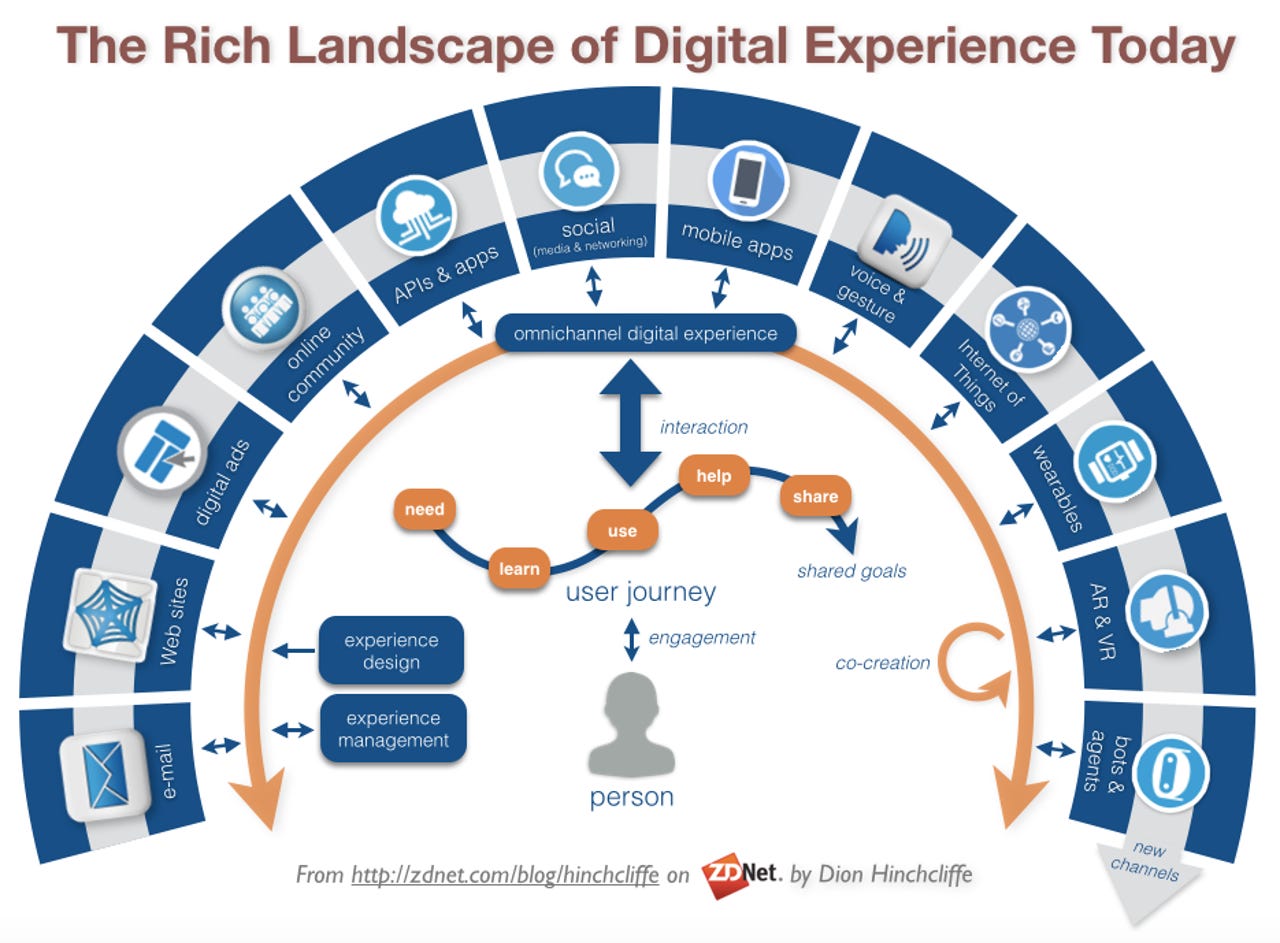

The bottom line is that organizations need to have a clear-eyed view of the digital experience landscape and what the major moving parts are today. Here's a round-up and brief assessment of the largest and most significant digital experience channels that most organizations must either a) address well today or b) be considering carefully for the future, listed in approximate order of initial emergence in the marketplace:

- E-mail. The volume of e-mail and number of inboxes is actually growing steadily in low single digits according to a recent Radicati Group report, though its relevancy is steadily diminishing in the face of so many richer and more situated messaging options. These days perhaps the most important use for e-mail in digital experience is to employ it as the onramp back into other channels, using it as a notification tool when something important happens in another digital channel or application. Why? Because the one thing that e-mail gets right better than any other communications technology is that it's fully interoperable with every other e-mail inbox in the world. It isn't a silo, like newer channels such as social typically are, and can still reach most people wherever they are.

- Web sites. Companies still need a Web site, and now it has to be fully responsive and include an easy way to manage content and participation for both the company and visitors. A corporate Web site also must link to other related digital experiences, such as social networking presence, mobile apps, and be able to contain virtual 3rd party assets such as mobile advertising and syndicated content, as appropriate. Interestingly, the cost of developing a capable Web site had been dropping steadily in years' past, like most other technologies, until recently that is, as the need for responsiveness -- yes, due to channel proliferation -- has driven the cost back up substantially.

- Digital advertising. Though it's sometimes not considered a part of digital experience proper, Web-based and mobile ads are often the "point of the spear" for an organization in terms of triggering the initial branded digital experience with the market, so I usually include it in digital experience strategies. Ads can route people to almost any kind of digital experience that's necessary to support shared value creation. Digital advertising is also increasingly used to monetize existing visitor traffic, whose untapped value is still left on the floor by most organizations.

- Online community. Perhaps the most strategic digital experience there is, online communities are focal points of high-value engagement at scale between businesses and their customers, as well as their business partners. While customer community is a critical digital experience to get right early on and develop as a foundation for digital engagement across all channels, it has also become essential to have for organizations to hold their stakeholders closer than in the past, as everyone else tries to draw them into their own spheres of digital influence. It's worth noting that the ROI measures of community are perhaps the highest of any digital channel, according to recent research.

- APIs + 3rd party apps. This model shows how profoundly different and powerful native digital strategies can be: Companies cannot and should not develop all the digital experiences that their customers will need. Nor do they need to. As I've long tracked in this space, opening up APIs to partners who have their motivations and will invest their own time and resources in creating 3rd party digital experiences can be a very successful strategy, though one that is still a challenging mindset for many traditional organizations.

- Social media and networking. Social channels are now the richest and most value creating of all the digital channels. Billions of pieces of content of every type imaginable are co-created daily by people and the organizations they are engaged with. It's now virtually mandatory to have presence on all the major social networks. Nowadays, however, the most highly engaged social channels are often niche services aimed at a specific interest or purpose. As an example, publishing companies should be involved with Goodreads, health care firms should be connected to Doximity, tech giants need to be on Spiceworks and green firms on Care2. Organizations' other digital experiences should be coordinated and connected with their social channels, and analytics tracked for opportunities/crises and NPS scores calculated regularly. Older social media like corporate blogs are still important channels and useful, but have largely been eclipsed by social network services in terms of scale and scope.

- Mobile applications. While I've been critical of mobile apps in the past for taking away much of what was so significant and valuable about the Web, they are a compelling way to provide many kinds of digital experiences that Web pages aren't as good at, such as location, video, voice, or very immersive experiences are involved. A good digital strategy can map out where it makes the most sense to invest in them.

- Voice and gesture. With Apple's Siri agent for the iPhone came out in 2011, it showed the industry, at least in early form, that a verbal conversation could be the entire digital experience. While voice agents haven't progressed as far as some have thought, my estimate is that it will become a critical aspect of digital experience as many more products and services being engaging via voice. Gesture is in the same boat, being largely relegated to gaming technology so far, but I've included it here as a digital experience that some industries, from video games to healthcare, must at least consider. I must confess that I'm biased towards gesture tech and I find my Myo digital armband is actually pretty useful to control presentations.

- Internet of Things. Almost every object in our lives is about to get connected. Each one will need an efficient, effective digital experience, often in combination. I explored my take on digital engagement and Internet of Things at my keynote last month (video) at @Things Expo. My main point was that the digital experience of interacting with so many connected devices -- another version of the engagement paradox -- is going to be a top priority for experience management and IoT to make effective for the foreseeable future. Companies will have to think very holistically -- and in a highly interoperable manner -- if they expect their IoT customer experiences to be seamless and seen as useful.

- Wearables. It is still the case that wearables have yet to really take off, and they likely will as some of the remaining issues -- from battery life to compelling and useful user experiences -- are addressed. Most organizations only need wearables on the radar, though some industries, especially those connected to human health or sports activity, need to be in advanced experimentation by now.

- Augmented (AR) and virtual reality (VR). Also in early days, these technologies will revolutionize digital experience, by making much more immersive and visually interactive. Early app stores already exist, especially notable is Oculus Rift's store (which calls its apps 'experiences') and critical mass is building. I believe that once the form factor is slimmed down and matured, both AR and VR will be a very popular way to digitally engage. Again, it must be on most organizations' enterprise technologies to watch list, with experimentation at least beginning. My favorite business example of virtual reality so far has been Marriott's VR travel teleportation experience back in 2014, which allowed visitors to their business hotels to virtually visit their other properties in more vacation-friendly locations.

- Bots and smart agents. Much hype has been dispensed about smart chat services like Facebook Messenger or intelligent chatbots. I've weighed in on this trend in-depth recently, and I favor them to be a leading model for next-generation digital experience, especially when combined with a voice user interface.

Clearly, there is quite a lot to consider here, and to reconcile with each other, which is one of the key points: Most organizations must spend as much time considering how to organize for modern, integrated digital experience, as executing well on it.

Please also note that the digital experience channels here are just the main ones that companies must consider. Most organizations have serious additional homework to do to remain well connected to their key stakeholders in digital channels.

For this, I recommend that organizations proactively develop roadmaps that cast a wide net to include all relevant candidate technologies where appropriate. Then a) conduct small experiments to validate emerging digital experience technologies, b) build effective digital solutions that actively encourage sustainably and self-evolving co-creation with their stakeholders, and c) begin investing seriously in more holistic, coordinated, and data-validated and guided digital experiences.

Additional Reading