The Roads Taken

It's been a few days since the news about iPhones (and other smartphones) storing device locations came out again. This time, however, it hit the mainstream press, rather than staying in the more refined heights of the computer forensics world - and simple tools for exploring the data followed quickly.

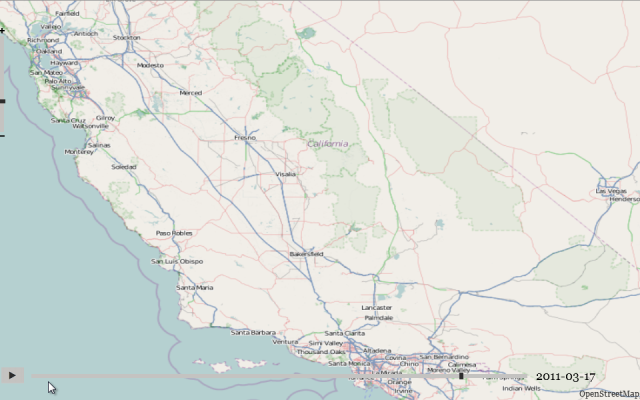

Here's a YouTube movie of some of my data, from a recent trip to the US attending a bunch of technology conferences. What's interesting is that even though I turn off my data connection while I'm abroad thanks to egregious roaming charges, my location's still being recorded.

So why is Apple doing this? Or for that matter, why's Google doing the same in Android, or Microsoft in Windows Phone? The answer's actually pretty simple - dis-intermediation.

Companies like Skyhook have used war driving techniques to build massive databases of cell tower IDs and WiFi hotspot signatures which then use to power a set of location services. Priced at fractions of a cent a lookup, those services are at first sight (and at the launch of your first phone) cheap. But when you're selling millions of devices a month, all of which are consuming data and location services, those fractions of a cent a look-up very quickly add up.

After a while it's cheaper to launch your own non-GPS location provider. But this is the real world, not the fantasy of 24 where all you need to do is hook into a mobile operator network to find just where a specific phone is hidden... Cell tower IDs aren't enough to locate a device, even if you're triangulating off two or more towers. So what's needed is something a little more sophisticated: a database of real world locations, tied to cell towers and signal strengths (and perhaps with a few WiFi SSIDs for luck).

So how do you make that database? And there starts the engineering-led process that ends up as a public relations fail, congressional investigations and all. Why not use the phones you're selling? After all, you've got an army of millions of sensing devices out there all chatting to cell towers and WiFi hotspots, and all using GPS to give their users an accurate position. Tie them all together, record a handful of positions per device per day, and then bundle them up in a huge anonymous database. All you need to do is craft some new user terms and conditions, and you're away.

That is, until you forget to delete the data when it's uploaded, leaving each device with a huge library of position information whether the users have signed up to give you data or not. Suddenly you've opened up a privacy can of worms, with law enforcement granted full access to everywhere a phone's been, and files open up for black hats to track down offices or homes.

Oh dear.

Still, it makes for an entertaining look at the roads taken.

Simon Bisson