There is no spectrum crisis

As part of its National Broadband Plan the agency wants to open up 500 MHz of new spectrum to bids, taking from TV and selling to phone carriers.

Not that those carriers appreciate any of it. They are furious that the FCC wants to impose net neutrality rules, or something like them, on their industry. They insist the bandwidth shortage, caused by the spectrum crisis, makes active management of the resource necessary.

Nonsense.

The answer lies in the 19th century.

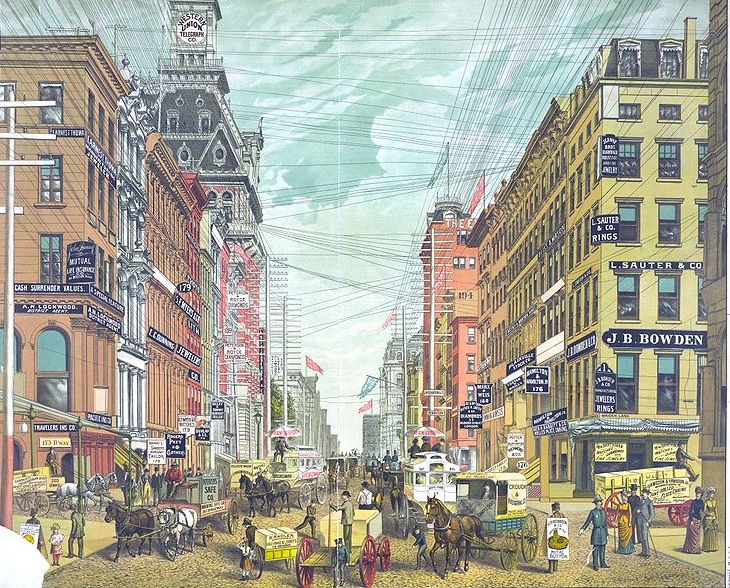

Back when telephony itself was a new idea, in the 1880s, lower Manhattan was filled with wires from competing companies, as this picture from the blog Ephemeral New York illustates. Once Alexander Graham Bell's patents expired in the 1890s, it only grew worse.

Lower Manhattan had a bunch of competing phone companies, but most places had none.

The reason was simple math. Manhattan had lots of customers who wanted service, all packed together. The countryside had far fewer people, and even if all of them bought service the cost of running wires was prohibitive.

The solution was the Bell System. In exchange for its monopoly, the companies of the Bell System took on an obligation to offer universal service, meaning a wire for everyone. The idea was to conserve a scarce resource, which at that time meant capital, and to manage it for the benefit of everyone.

Today we have an artificial shortage of spectrum. The competing cellular networks are like those wires in the old New York picture. They are all doing the same thing, pretending to compete, but in fact they're redundant.

If all our electromagnetic spectrum were managed the way bankers like J.P. Morgan and industrialists like Theodore Vail managed scarce capital, the picture would change.

Build one network, based on TCP/IP, connected as much as possible to the wired Internet, and let anyone go into the business of selling access to that network at a regulated price. The model for this is the Internet, expressed in the WiFi standards, which define connectivity based on equipment, not spectrum ownership.

Instead of having four redundant networks, an oligopoly which extends its reach into the equipment space, you have one utility from which many companies can re-sell services. One Interstate Highway between Atlanta and Birmingham becomes far more efficient than four competing toll roads.

More important, you have a more competitive market. Today's carriers become more like trucking companies. Cell phones become more like WiFi routers, with manufacturers selling directly to consumers rather than through service providers. Service providers re-sell capacity to customers large and small at the most competitive rates possible, because anyone can get into the game.

The whole bandwidth shortage, and the resulting arguments over net neutrality, are an artificial construct, composed mainly of "free market" ideology tied to an obsolete regulatory scheme. Change the regulatory scheme and the problems go away.

It's all a question of political will. The wireless Internet should look like the wired one. The controlling principle should be the public interest, not the private interests of those who were mistakenly sold what should have been kept.

Buy it back.