Unchaining the opportunistic programmer

One of the most wonderful elements of Open Source is that the free availability of good tools and balanced licenses means that motivated people can create interesting things. The entire Open Source landscape, on any Operating System,is fundamentally driven by this ethos: great tools, great people and a great environment make even greater things happen.

One of the most wonderful elements of Open Source is that the free availability of good tools and balanced licenses means that motivated people can create interesting things. The entire Open Source landscape, on any Operating System,is fundamentally driven by this ethos: great tools, great people and a great environment make even greater things happen.

Anyone who has been around these Open Source parts for a reasonable chunk of time will have come across the many and varied chunks of Open Source lore that get bandied around. We talk about "scratching your itch" and that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow". We round out these observations with an encouragement to "release early, release often" and that "if you see a bug, file a bug". Each of these juicy nuggets of wisdom each points to an underlying culture of embracing the opportunistic programmer.

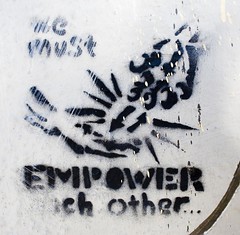

Opportunistic programmers do exactly what it says on the tin: they find opportunities to write programs. They are a subset of a wider demographic of people that when enabled with tools and knowledge can creatively think of and ultimately implement solutions to common problems. Opportunistic programmers are typically not interested in writing large office suites, web browsers and email programs. Instead, they like writing small, fun and useful little programs. They buy a new device and need a tool to manage it: they write it. They want to be able to track their workouts better: they write it. They need a tool to manage their TODO list: they write it. Opportunistic programmers revel in the fact that they are empowered to solve problems not only conceptually but practically.

Although the culture and heritage of Open Source is fueled by opportunistic programmers, in many ways we have regressed as time has gone by in supporting them. Said heritage is stuffed to the gills with full-on, beardy, hardcore programmers, complete with mad skills and über-technical temperament. In such a comprehensive development culture, the workflow is often underlined with an all-buttons-on approach in which flexibility and extensibility is optimized at the cost of ease of use and a straight-forward entrance to the workflow's conveyer belt. What results is a development environment that is approachable if you are willing to put in the time to understand all of these buttons and obscurities, but a right-royal pain in the arse if you are the very opportunistic programmers that I am talking about.

I myself have experienced this. I am the definition of an opportunistic programmer. My main profession is not coding, but I do like to write useful little programs. I understand my limitations, and I am comfortable with them: I am about as suitable for large application development as a gibbon is. In the same way I love how Python lets me ignore the horrible housekeeping work required in C, I have also felt that the same approach needed to be taken to all the elements that surround the core process of writing code; elements such as creating projects, adding files, editing code, creating user interfaces, ensuring different files work together, testing, debugging and packaging. Each of these things has traditionally been complicated, monotonous and ultimately distracted away from the primary attraction: writing code that does cool things to scratch an itch.

Enter Quickly

Someone else who had felt this kind of pain was Rick Spencer, the leader of the Ubuntu Desktop team at Canonical. When he came to visit me for a a set of meetings in my home town, he shared an idea for a tool he called 'quickly'. His idea was to optimise the development workflow using a set of opinionated decisions. There are countless ways of making programs in Linux and more specifically in Ubuntu: you can code in C, Python, Perl, or C#, use GTK, Qt, or wxWindows, hack code in a variety of text editors and development environments, use different source control systems and whatnot. Rick was keen to make a set of choices in each of these component domains and have a tool that optimized around these choices. He worked on his idea, gathering help from the community (include an incredible community member called Didier Roche), and thus Quickly was born.This is how it works. I can first type in 'quickly create ubuntu-project awesomeapp' which generates a program called awesomeapp. This generates a chunk of code in a project that presents a window, complete with menu bar, status bar, dialog boxes and other common components. I can then edit all the code files by simply running 'quickly edit' or edit the user interface files with the graphical Glade application by running 'quickly glade'. I can test my changes by running the program with 'quickly run'. Not only this, but Quickly can also generate an Ubuntu package with one command by running 'quickly package' and even publish a package to a Launchpad Personal Package Archive (which is like your own personal archive of packages) by running 'quickly release'. With this simple set of options, Quickly automates everything from loading the source code into a text editor right up to packaging and release your program. This helps me keep my focus on writing code and having fun writing it.

At the heart of Quickly is lowering the bar for opportunistic programmers, it means that we should get a more diverse range of applications. Compare and contrast the Linux development ecosystem with that of the iPhone. In the iPhone world, developers feel empowered to write something as complex as a large scale application that helps a business tick or something as trivial as pushing a button and getting a fart noise. By unchaining the opportunistic programmer, it means that silly, irreverent, fun and specialized programs are as welcome as big, serious applications. This is the thing that most excites me about Quickly: it has the opportunity to build a diverse environment of application choice for users.

A Bacon Case Study

I am a good example of how an opportunistic programmer has been empowered. I have so far written three applications. I first wrote Flarebook, a simple graphical front-end for managing my Amazon Kindle in Ubuntu, and sharing notes and content from it. I then wrote lolocopter, a silly little program that allows you to trigger a series of comedy sounds, particularly apt when working together in an office. Lolocopter was even extended to play the same sound on a series of laptops at the same time using the GStreamer framework; a feature known as the 'Denial Of LOL Attack'. Finally, and most usefully, I created a program called Lernid which is designed to make online learning events based on IRC much easier. I wrote this specifically to help improve how we run our Ubuntu Open Week and Ubuntu Developer Week.I can safely say that if it were not for Quickly, I would never have written these programs. It helped me not only get up and running quicker, but it also helped me publish and share my work with others. As an opportunistic programmer, it is just what I needed. I am excited to see how this will help other such programmers do the same thing.