We're told data breaches cost millions on average - but this security study disagrees

The study shows that cyber incidents cost firms 0.4 percent of their annual revenues, dwarfed by issues such as billing fraud.

Far from running into millions, the average cost of a data breach is less than $200,000, or roughly what firms are spending on IT security systems, according to a study from non-profit thinktank RAND.

The study, published in the Journal of Cybersecurity, challenges the much higher cost estimates provided by the Ponemon Institute. This year that research organization put the average cost of a breach at $4m.

RAND policy researcher Sasha Romanosky analyzed 12,000 events between 2004 and 2015 and found that the cost to each firm was on average less than $200,000. This figure is on a par with the 0.4 percent of revenues that firms in the study spent annually on IT security.

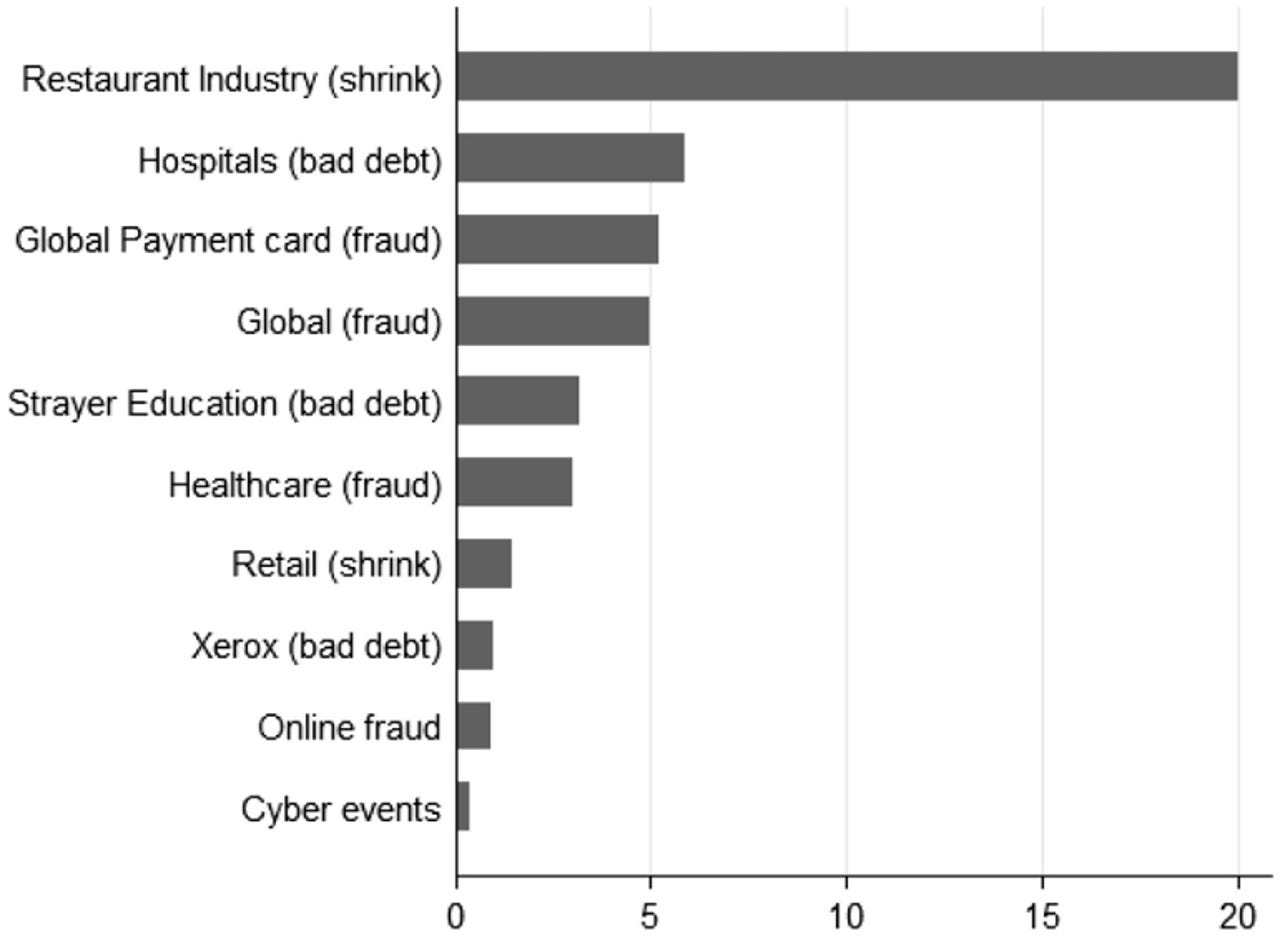

"We find that the typical cost of a data breach is less than $200,000, far lower than the millions of dollars often cited in surveys, eg, Ponemon 2015. Moreover, we find that cyber incidents cost firms only 0.4 percent of their annual revenues, much lower than retail shrinkage of 1.3 percent, online fraud, 0.9 percent, and overall rates of corruption, financial misstatements, and billing fraud, five percent," the author said.

In other words, the low direct costs of remediating a breach appear to offer little incentive for firms to spend more than they do currently. That situation goes some way to explaining why governments see the need for laws such as Europe's new data-protection regulation, which threatens firms with fines of up to €20m or four percent of global annual revenues.

In the US context, Romanosky wanted to find out whether, with the NIST's cybersecurity framework signed by president Obama in 2013, firms will voluntarily improve security controls.

Romanosky sourced data for the study from Advien, a US insurance analytics firm that sells data to insurance companies and has a database of 300,000 incidents.

He also found that credit-card numbers and medical information were the most commonly compromised information, while malicious incidents accounted for 60 percent of all incidents. Meanwhile, 1,700 incidents resulted in legal action, with half brought by civil suits and 17 percent through criminal prosecutions.

Romanosky's findings are consistent with a recent analysis of the remediation costs of several high-profile data breaches in the US, including those against Sony, Target, and Home Depot. Each company's costs ran into tens of millions of dollars, but amounted to less than one percent of their respective annual revenues.

However, some breaches are relatively expensive. The breach of UK ISP TalkTalk, which was caused by a simple coding error, cost the firm £60m, which amounted to three percent of its 2016 revenues. Its breach prompted recent calls for CEOs to face pay cuts where lax security is found.

The author of that analysis, New York-based political economist Benjamin Dean, concluded that firms have little incentive to invest in security because others bear the costs of risks they take.

For example, credit unions claimed it cost $60m to replace cards exposed in the Home Depot breach, which was more than Home Depot's final remediation cost even before insurance payouts.

Romanosky isn't certain whether there are sufficient incentives to invest more in data security. He speculates that the cyber insurance industry may be "driving a de facto national cybersecurity practice across insureds", but he hasn't found evidence that firms are responding by investing in cybersecurity.

However, with breach costs so low, he believes it will be difficult to convince firms to voluntarily adopt the US NIST's cybersecurity framework.

Read more on security

- Krebs on Security booted off Akamai network after DDoS attack proves pricey

- Cybersecurity accelerator gives startups the chance to work with GCHQ spy agency

- Google Safe Browsing beats rivals but still only flags up 10 percent of hacked sites

- Drupal patches multiple security flaws in core engine

- IBM lambasted by ABS for failing to handle Census DDoS

- TechRepublic: Report: The top 6 industries hit by ransomware

- CNET: How to find out if you're at risk in Yahoo hack