Who really wins from Facebook's 'free internet' plan for Africa?

Facebook caused a storm of controversy in India when it launched its Internet.org app, offering free access to a suite of websites including Facebook's own pared-down 'zero rated' service. Net neutrality advocates have been up in arms, and their arguments have gained enough traction to cause a number of Indian content providers, including the Times Group and NDTV, to step away from the initiative.

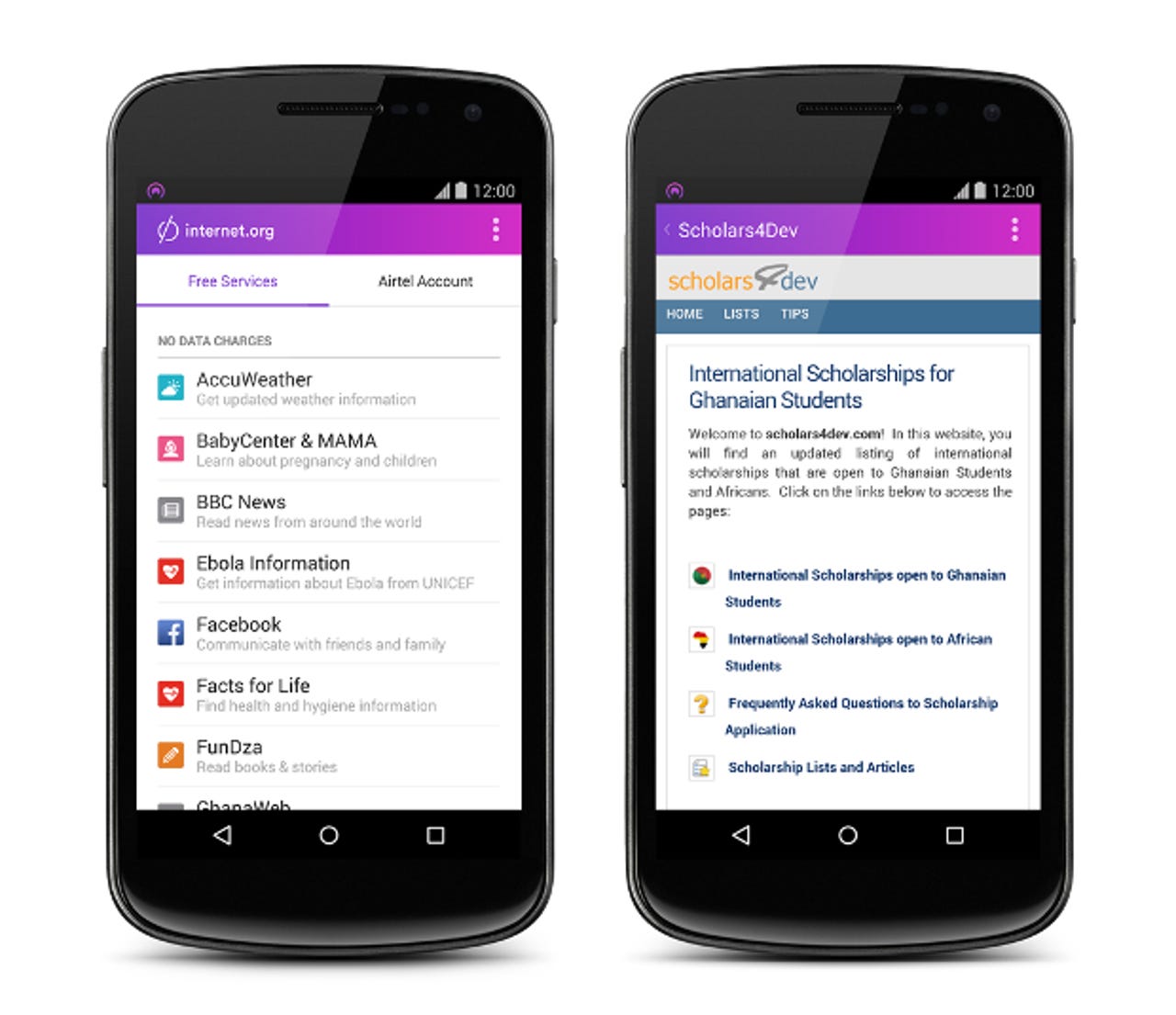

But that hasn't stopped Facebook Zero and Internet.org from expanding into an even less developed market: Africa, where operators in a growing number of areas are offering zero-rated versions of Facebook to their users. Internet.org is currently available in Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia; several others offer Facebook Zero on its own.

Writing in the Hindustan Times, Zuckerberg tried to convince India's increasingly vocal critics that his company was on the side of net neutrality. "It's an essential part of the open internet, and we are fully committed to it," he wrote, adding that "to give more people access to the internet, it is useful to offer some services for free. If you can't afford to pay for connectivity, it is always better to have some access and voice than none at all."

Read this

Getting more people online, if only on a limited number of sites, has certainly paid off for Facebook: although the causality is difficult to determine, the number of African Facebook users increased by 114 percent in the first 18 months after Facebook Zero was launched in 2010, according to internet tracker oAfrica.

Facebook's African journey has not been as ideologically fraught as in India. Danson Njue, telecoms analyst for research firm Ovum, points out that African countries generally have little to no regulation to protect net neutrality, so zero-rated services are unlikely to face the same sorts of legal battles they have in India.

But while it might not attract as much attention, zero-rating, say net neutrality advocates, is every bit as worrying in Africa as it is in Asia. In countries with very low internet penetration rates, it could be even more so.

"Current users understand that the revolutionary nature of the internet rests in its breadth and diversity," writes Raegan MacDonald, European policy manager for the advocacy group Access, on the group's blog. "The internet is more than Wikipedia, Facebook, or Google. But for many, zero-rated programs would limit online access to the 'walled gardens' offered by the web heavyweights. For millions of users, Facebook and Wikipedia would be synonymous with 'internet'."

Indeed, studies have found that users in developing countries often conflate Facebook and the internet; Quartz found that a startling percentage agree with the statement, 'Facebook is the internet'. For users without data plans whose only access to the online world is through Facebook, these numbers are likely to be even higher.

"No corporate or single platform -- whether it's Facebook or Wikipedia -- should be put in charge of curating access to the world's information," writes MacDonald, who sees the same problem with Wikipedia's zero-rated service.

Granting zero rating to majors like Facebook and Wikipedia, critics argue, also makes it more difficult for smaller local companies, which don't benefit from such prioritization, to get access to users. MacDonald says the long-term effects would be to quash innovation and competition.

But for the moment these arguments don't seem to have had much impact on the African mobile carriers striking deals with Internet.org, which include Bharti Airtel in Kenya and Millicom in Tanzania. Along with the edge they're hoping the service will give them over their competitors, Ovum's Njue says carriers are hoping Facebook Zero, while free, will eventually boost data sales as curious users are tempted to click through to links and photos for which data charges apply.

And although Facebook Zero works on features phones, he adds, "telcos are really trying to drive up smartphone acquisitions in their networks," and steering users toward mobile internet use means steering them towards more sophisticated handsets as well.

Speaking at this year's MWC trade show in Barcelona, Zuckerberg did his best to assure mobile carriers that zero-rating is as good for their business as it is for his own. "Facebook's Internet.org is helping carriers around the globe get more people to pay for data plans by giving them a free sample," he said. "That is the future business, and I think that everyone is excited about that."

Read this

But not all mobile carriers are buying into it. The Wall Street Journal reported in March that new data users haven't been making up for the call and texting revenue lost to Facebook's free messaging service.

"Telcos in Africa will see these OTT players as a direct competitor, so they are treading carefully," says Njue. "They are not very sure that giving free services is going to help them in any way. The assumption is that when users enjoy the free services, some of them might also sign up for data plans to access other services. But it's not automatic." That may explain why, five years after Facebook Zero was launched, only four African countries have signed up to Internet.org.

While it may push those who can afford it into data plans, at the end of the day, zero rating won't solve the underlying problems that create Africa's yawning digital divide, says Ephraim Kenyanito, who works with Access on the continent. Serious investment needs to be put into providing people with the real, complete internet, "not these short-term fixes", he says. "This is just a Band-Aid."

Read more on this story