Wind, wind everywhere. Who needs any other energy source?

There's enough wind blowing out there to provide more than 100 times the amount of electricity than the world currently uses.

According to a new study by the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford University, reported in Nature Climate Change, "surface winds" alone could do the trick by furnishing 400 terawatts of generating capacity. That's more than 20 times the planet's current 18 terawatt demand, the study states. (18 TW is a lot higher than "installed capacity" figures that I'm familiar with, but never mind - the point is that there's enough wind to satiate everyone and legions of others).

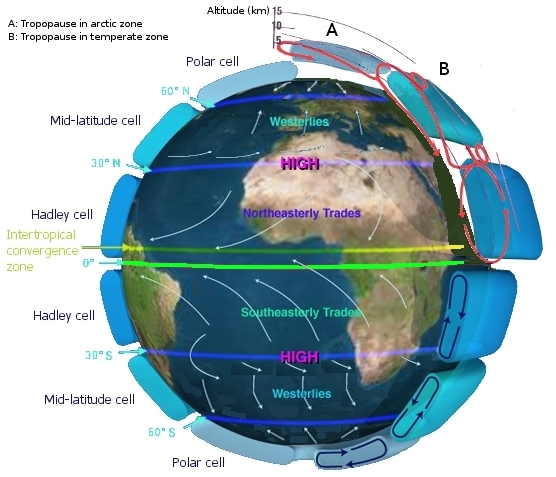

Throw in high altitude wind - the sort reachable via kite or some other airborne device rather than through land-based wind towers - and you're looking at an embarrassment of riches. Those loftier currents blow harder and more steadily. They reside anywhere from a thousand feet or so, up to the miles-high jet stream, and could add another 1800 terawatts, according to Carnegie.

But be careful before littering the skies with turbines. If you mess with nature's breezes too much you could actually alter the climate - an ironic possibility given that the point of installing wind turbines in the first place is to cut down on fossil-fuel induced climate change.

That would certainly be the case if you were to build all those 2200 terawatts of wind machines. "At these high rates of extraction, there are pronounced climatic consequences," the study notes.

However, Carnegie assures us that if we were to simply stop at today's global power level of 18 terawatts, then "wind turbines are unlikely to substantially affect the Earth's climate." One caveat: the turbines would have to be distributed, and not clustered in concentrated areas.

How much would it cost to get those 18 terawatts into the sky? Well, now you're talking about the true impediment. As the study points out, "It seems that the future of wind energy will be determined by economic, political and technical constraints, rather than global geophysical limits."

Let's see how the financial and political winds blow.

Image: NASA via Wikimedia.

A swirl of wind stories on SmartPlanet:

- Scotland plans world's largest offshore wind farm

- Becalmed: Wind orders die down

- Harnessing the jet stream for wind turbines

- U.S. approves wind power for 1 million homes

- Make way for renewable energy’s blade runner

- Donald Trump on wind energy and tourism: ‘I am an expert’

- Donald Trump blasts wind in Scotland

- US, UK join forces on ‘floating’ offshore wind turbines

- Floating wind farm on Fukushima’s horizon

- U.S. opens Outer Continental Shelf to wind power

- Siemens bags another offshore wind project

- Looney threat to world’s largest offshore wind farm

- Wind turbines: Pretty in pylon?

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com