Facebook's giving away servers for AI: So what does it get in return?

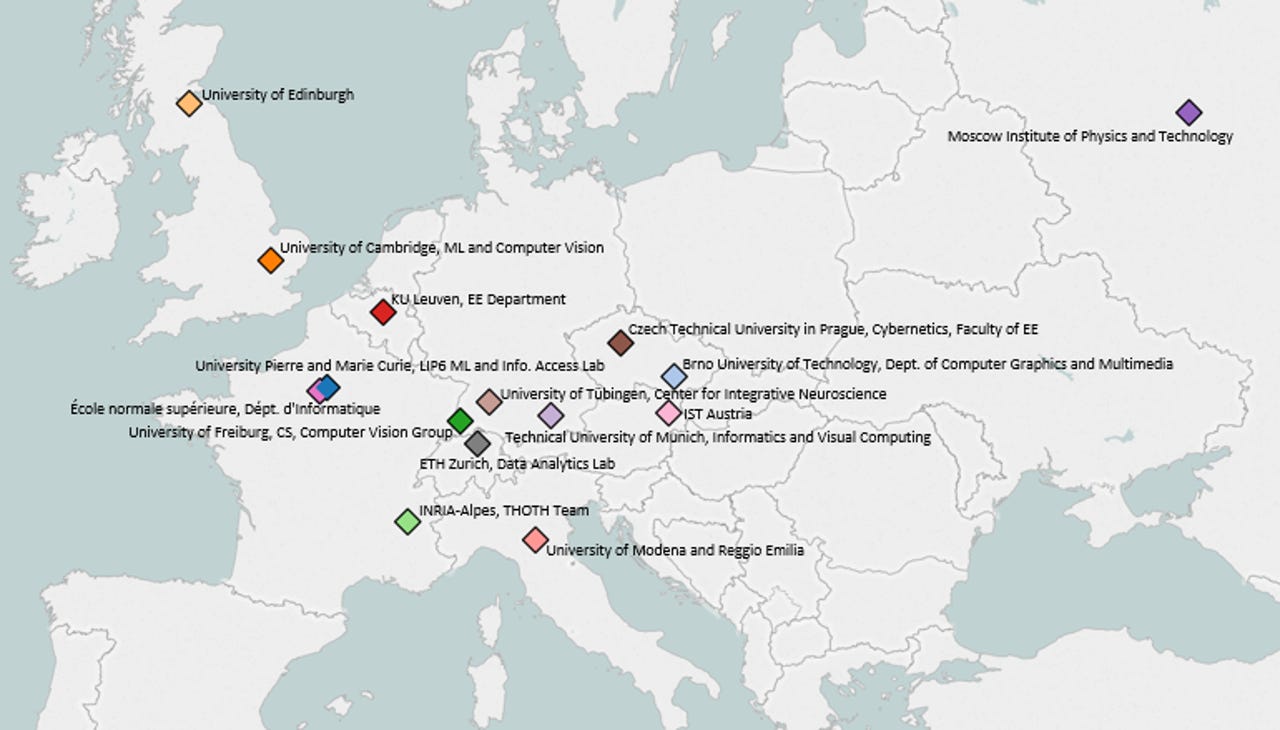

Facebook is distributing 22 high-powered GPU servers to 15 research groups across nine European countries.

Just east of the Belgium capital, Brussels, Marian Verhelst's microchip research group at the University of Leuven anxiously awaits a large shipment of supercomputing servers from Facebook's Silicon Valley headquarters.

Verhelst, an assistant professor of electrical engineering at the university known as KU Leuven, plans to employ the deep-learning potential of these computers to help develop more advanced processors.

As part of a global research partnership to stimulate artificial-intelligence research into deep learning, Facebook is donating 22 GPU-accelerated computer servers to researchers in nine countries across Europe.

Facebook has already donated four additional GPU servers to TU Berlin. And at the end of August, Facebook announced the list of the servers' final recipients, which included the electrical engineering department at KU Leuven.

GPU computers include a graphics processor unit, or GPU, which dramatically speeds up mathematical computations compared with computers without such chips.

Deep learning, a popular machine-learning technique based on neural networks, requires intensive computing power and runs relatively slowly on standard computers. But GPU computers can run the code more rapidly by routing most computation-heavy instructions to the GPU while letting the normal central-processing unit manage the more routine tasks.

Lately, deep learning has been causing a talent arms race among large tech companies in the US, where firms such as Facebook and Google are working to refine deep-learning algorithms to improve products ranging from speech recognition to content personalization.

But the battle for talent is being largely fought across the Atlantic, as these companies scour Europe for bright researchers to support, in return for the prestige of associating their brands with the researchers' advances.

After all, an engineer from Google's Zurich office conceived of Google's DeepDream, which has since become a dominant force in the field. Missing no opportunity to harness more European talent, Google established a machine-learning research center in Zurich in June. Could Facebook's direct server donations breed similar innovation?

"These servers will allow us to do the research much faster because they can compute the algorithms very efficiently," Verhelst says.

Verhelst specifically aims to use the Facebook servers to define a deep-learning architecture that requires the fewest number of computations. This approach, she says, could reduce the power consumption and size of deep-learning hardware to the point where it can fit into a mobile device.

Besides Verhelst, four other engineering professors at KU Leuven will use the incoming Facebook servers for a range of artificial-learning tasks, from video image recognition to machine-learning.

In return for the GPU servers, Facebook asks that the researchers make all their research findings and datasets open source, so that anyone in the artificial-intelligence research community can learn and build from them. Currently, Facebook uses deep-learning technology to improve image recognition and personalize users' feeds.

Sharing machine-learning research publicly is now the norm for the big tech companies, which hope to provoke more advances elsewhere in the research community.

Facebook open-sourced its first library of artificial-intelligence code on GitHub in August. Called fastText, the library contains methods for computers to recognize sentences rapidly and categorize them into classes.

Microsoft published its Computation Network Toolkit, or CNTK, on GitHub in January, but it has been available under an open-source license since April 2015. Google published its TensorFlow machine learning platform on GitHub last November.

"There's no monopoly on ideas. The field advances quickly when large and diverse sets of researchers build on top of each other's work. The larger the interacting community, the faster the progress," wrote Facebook AI Research engineering director Serkan Piantino and research lead Florent Perronnin in a blogpost to announce Facebook's partnership with European institutions in February.

While open-source code encourages collaboration, specifically focusing research relationships in continental Europe might be a judicious move for Facebook.

Google and Microsoft have already tapped the UK for artificial-intelligence research talent. In 2014, Google bought London-based deep-learning startup DeepMind, and Microsoft has an established research lab in Cambridge.

Meanwhile, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft have been financially supporting US researchers for years. Facebook's formal European outreach program could help cultivate the type of professional connections in Europe that these companies usually make with home-grown talent.

Google is more direct about why it is investing in Europe-based research: "Europe is home to some of the world's premier technical universities, making it an ideal place to build a top-notch research team," Emmanuel Mogenet, head of Google Research, Europe, wrote in a blogpost about its new Zurich-based machine-learning research group in June.

KU Leuven is among the high-caliber technical institutions that fuel artificial-intelligence research in mainland Europe. Other big names are the University of Tübingen, the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Lausanne and Zürich, and the French Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation.

Verhelst and the other professors at KU Leuven expect to receive their Facebook servers in the coming months.