Forget Neuralink: This less invasive brain implant company is recruiting trial participants

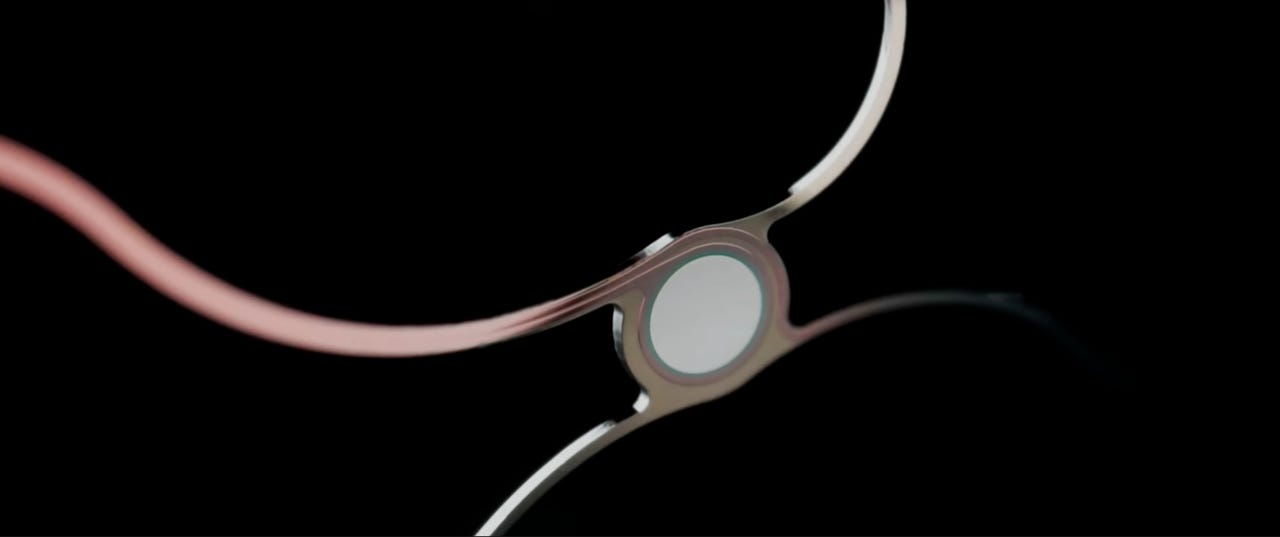

A visualization of Synchron's stentrode technology.

Even though brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are still an emerging part of neurotechnology, Neuralink, Elon Musk's BCI startup, has dominated headlines about the space. But rival company Synchron is taking steps to advance.

In a release on Monday, the company announced a new registry to recruit participants before its next phase of clinical trials. Synchron initially received FDA approval for human testing in July 2021, and as of last year, has implanted its device in six US patients. Before being greenlit for US testing, Synchron had been tested in four Australian patients. By contrast, Neuralink only received testing approval in May 2023, and has been tested in one patient.

Also: If we put computers in our brains, strange things might happen to our minds

According to Synchron's website, its BCI "aims to restore the control of a touchscreen for patients with limited hand mobility using only their thoughts." Both Synchron and Neuralink are intended for people with paralysis or other motor impairments.

"There is a grass roots movement happening with BCI," said Synchron CEO and Founder Tom Oxley. "We are creating an avenue for potential users and their physicians to engage and stay connected while we prepare for the next stage of clinical trials."

How it works

Synchron's device takes a less invasive approach to BCIs than Neuralink by innovating on a common medical technology: the stent, a tiny mesh tube used to keep compromised pathways open in the body. After a heart attack, for example, someone might need a stent to hold open weakened blood vessels.

Synchron recreated traditional stents with sensors that record brain activity, including thoughts. Connected to a computer via Bluetooth, it then turns those thoughts into texts, emails, and other actions they'd be unable to take with their fingers. The result is what the company calls a stentrode. Like Neuralink, it's fully internal to the body.

A 2020 report from the company stated that Australian patients testing its first-gen device could type 16 characters per minute on average.

Also: 3 ways AI is revolutionizing how health organizations serve patients

"BCI technology enables individuals with motor impairment to regain independence," said principal investigator David Lacomis, M.D., in the announcement. Lacomis is also the Chief of the Neuromuscular Division at UPMC and Professor of Neurology and Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh. "By controlling digital devices through one's own thoughts, BCI offers a transformative path towards performing daily tasks with greater ease and efficiency. From communication to accessing essential services online, BCI technology represents a ground-breaking frontier for individuals and their families."

Why it matters

Unlike Neuralink, which must be surgically inserted into the brain by a robot, Synchron's BCI is implanted via a patient's jugular vein and rests on the motor cortex through a minimally invasive procedure. According to Synchron, this approach means no brain surgery, and low risk of tissue rejection: as with normal stents, the body can easily absorb the stentrode, making it more comfortably permanent.

By designing the stentrode to be easily insertable in a catheter lab (as opposed to an operating room), Synchron hopes the device will be accessible to many more patients than those that require neurosurgical intervention.

The registry is intended to encourage physicians to start a dialogue with eligible patients and their families ahead of this next round of trials. Synchron told Reuters that 120 clinical trial centers have already expressed interest in assisting the study. Neither Neuralink nor Synchron has received full FDA approval to go to market yet.

You can learn more and join the registry here.