How do tech giants know so much about you?

It can be disconcerting to receive ultra-targeted ads from the sites we use regularly – but how do these sites seem to know so much about us? An in-depth study across the five largest tech companies throws some light on just how much they know.

Salt Lake City, UT-based custom e-commerce signs provider Signs has drilled down into how much information the major tech giants of our time collect about you.

It wanted to discover how much Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon (FAMGA) knows about you – and its 20 questions quiz shows how little we really know about them.

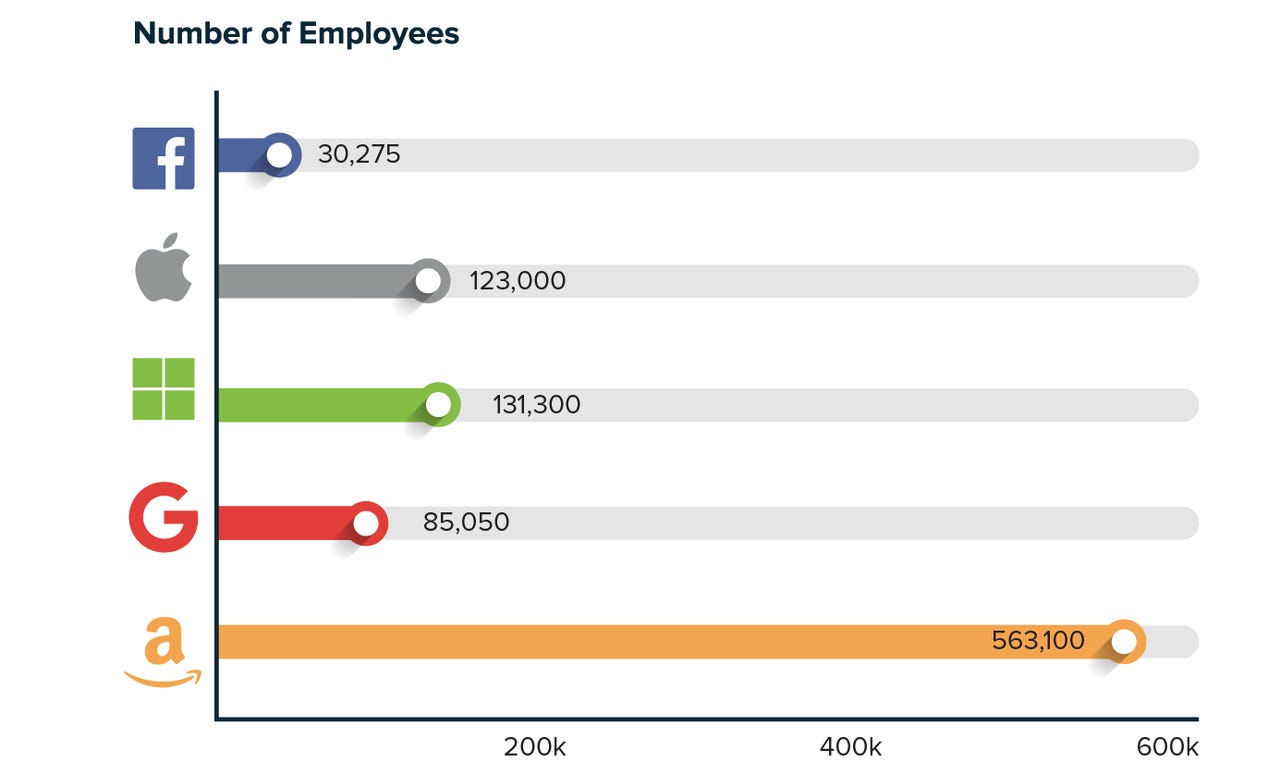

The findings show that Facebook, according to 2017-2018 revenue reports and forecasts, earns almost $106,000 per minute. The company has around 30,000 employees, and knows a lot about you.

Facebook can gather a pretty good idea of where you live based off of your IP address, geo-tracking through your mobile phone, and locations provided by your friends. One-third of all divorce filings in 2011 in the US contained the word 'Facebook'.

Apple, which earns almost $722 million each day, can see your iPhone's number through your carrier, and sells an average of 31 Macs per minute. Around 123,000 people work at Apple globally. Half of all households in the US own at least one Apple product.

Microsoft with over 131,000 employees earns around $12.5 million per hour has 400 million devices running Windows 10. There are three billion minutes of calls made each day by Skype users, and one in five people use Bing as their search engine.

Google is worth over $302 billion and earns over $4,348 per second. It has 85,000 employees around the world. Over 1 billion people use Gmail, and chances are your email address was created through Google.

Google can also identify your online activity through the YouTube videos that you watch, the ads you click, and websites visited to determine what you like.

Amazon earns almost $643.5 million per day, which would enable it to buy 261 Boeing aircraft, launch 17 shuttles into space or hold a Netflix subscription for almost 271 million years.

The company owns 43% of all e-commerce market share. It is the largest company with over 563,000 employees.

The companies that make up FAMGA are considered to be the most valuable brands in the world. Facebook has a higher revenue than the GDP of Greenland, Libya, Honduras and Iceland, whilst Apple has higher revenue than the GDP of New Zealand.

So how did they get so rich?

Data. Each company holds a lot of data about you. All of the companies know your name, phone number, and email address. Only Apple does not collect your home address, but receives it if you provide it in your Apple ID account.

Every company across FAMGA can learn your hobbies and interests except Amazon, but Amazon does track your purchase and browsing behaviour to get a good idea of your purchasing preferences and therefore your hobbies.

Featured

Amazon and Apple do not have information about your family and friends – unless you send gift certificates, or purchase items to send to friends.

Facebook tracks which of your friends you interact with the most, which enables it to recognise which of your friends you are closest to. Facebook also has the ability to discover your relationship status and sexual orientation.

Each company knows what type of phone you have, and which gender you are. They each could determine your eye colour based on the profile pictures you have submitted in the past.

Microsoft's acquisition of LinkedIn means it can easily discover your current job and your employment history.

Only Amazon and Microsoft do not require your birthday, and Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon do not know your political views. Apple, Google and Amazon do not appear to know your education level either.

All companies have the ability to track your browsing history, although Amazon can only track the website visited before Amazon and the website you visit after leaving the site. All companies in FAMGA store your credit card information.

All companies except Facebook record voice commands spoken to voice assistants, and Facebook says it will only access your phone's microphone if given permission through the use of specific features that require audio – despite rumour that it listens to your conversations.

These are staggering figures, all due to our insatiable appetite to stay connected to people, buy online, own the latest model of hardware and software, and discover the world around us.

The growth of the FAMGA companies seems like an ever-increasing trajectory with no serious competitors in sight.

But, as always, there may be a little-known competitor rising swiftly, ready to steal market share, and become as prominent as the FAMGA group.

Knowing who this will be could make the savvy investor a lot of money indeed.

Related content

Americans want an internet bill of rights to protect their online data

The US is cracking down on data collection and privacy laws – but what do Americans think about their internet rights?

Quarantine and chill: Here's the information the Netflix stores about you

With a growing number of people around the world self-isolating at home, people are looking for ways to keep themselves entertained. What better way than binge-watching the TV series you have been meaning to but did not have the time?

Alexa, you're scaring me: Study reveals top tech-driven concerns

Concerns about crimes and robberies have been around since the beginning of time. But our online world poses just as many threats and might even be scarier.

Here's why more US employees self-censor social media posts

Our online presence has infiltrated the workplace, but is what we post affecting our promotions at work?

Here's why more US employees self-censor social media posts

Our online presence has infiltrated the workplace, but is what we post affecting our promotions at work?