How Microsoft tracked down a spy who leaked its secrets

[Updated March 20, 3:20PM, with Microsoft statement and timeline]

Here’s a pro tip if you’re planning to get into the industrial espionage business: Don’t use your company’s free email, file storage, and messaging services to do the actual business of transferring that same company's trade secrets to a shadowy figure overseas.

That advice comes courtesy of the very bad example set by Alex A. Kibkalo, a former Microsoft employee who was charged this week with a single count of violating Title 18, United States Code, Section 1832, Theft of Trade Secrets.

According to an affidavit from FBI Special Agent Armando Ramirez III, a disgruntled Kibkalo stole top-secret source code and software development kits, pre-release hotfixes, and documents from Microsoft. He then used Windows Live Messenger to send links to the stolen files, which he had placed in his personal Windows Live SkyDrive account. And for good measure, he sent email messages with additional details to the Hotmail address of his contact in France.

The French Windows enthusiast, widely believed to have used Canouna as his alias, developed quite a reputation during the months leading up to the release of Windows 8, when he became a star in underground circles with leaks of information and code.

According to the FBI, Microsoft’s Trustworthy Computing Investigations department (TWCI) had been trying to track down Canouna’s true identity but had failed. They could not determine if the blogger was an external party obtaining information from a contact within Microsoft, or whether the blogger was a Microsoft employee.

Around September 3, 2012, Canouna sent an email to a person in Redmond, allegedly including some sample code from the Microsoft Activation Server Software Development Kit and asking if the recipient could help him “better understand its contents.” The outside source, who asked to remain anonymous, contacted Microsoft’s Steven Sinofsky instead.

Four days later, on September 7, 2012, the FBI says Microsoft acted:

The source indicated that the blogger contacted the source using a Microsoft Hotmail e-mail address that TWCI had previously connected to the blogger. After confirmation that the data was Microsoft’s proprietary trade secret, on September 7, 2012 Microsoft’s Office of Legal Compliance (OLC) approved content pulls of the blogger’s Hotmail account. [emphasis added]

Those email messages in turn led to instant messaging conversations and links to files shared on SkyDrive. Every piece of data was stored on Microsoft servers using an account allegedly linked to Kibkalo.

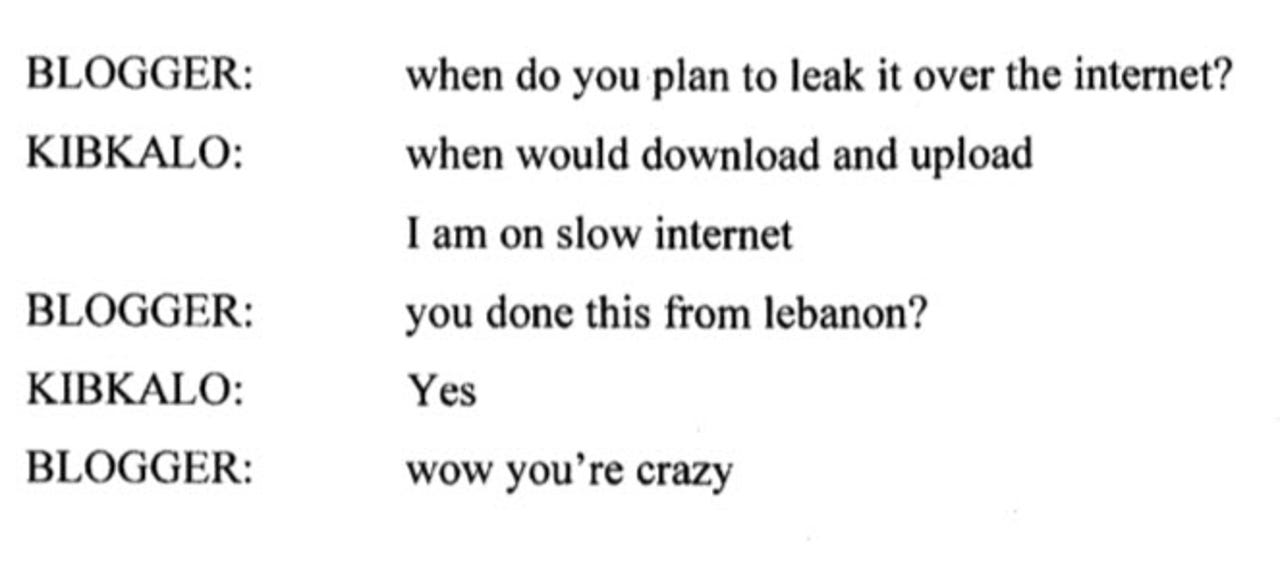

And there's no question that both parties knew they were breaking the law, as this snippet of conversatrion shows:

Three days after that exchange, on September 24, Microsoft investigators hauled their employee, Kibkalo, in for two days of questioning.

If the messages and files in question had been transferred using Gmail and Dropbox, Microsoft would have probably asked for and received court orders to get access to these communications. But because Kibkalo and his French connection had used servers that are run by Microsoft, the company was able to exercise the rights it had reserved in section 3.5 of the Microsoft Services Agreement:

Content that violates this agreement … or your local law isn’t permitted on the services. Microsoft reserves the right to review content for the purpose of enforcing this agreement. [emphasis added]

In its Code of Conduct for Microsoft services, which is part of the agreement mentioned in that section of the TOS, Microsoft expressly mentions "software piracy" under the Prohibited Uses section.

Microsoft Online Privacy Statement includes similar wording:

We may access or disclose information about you, including the content of your communications, in order to: (a) comply with the law or respond to lawful requests or legal process; (b) protect the rights or property of Microsoft or our customers, including the enforcement of our agreements or policies governing your use of the services; or (c) act on a good faith belief that such access or disclosure is necessary to protect the personal safety of Microsoft employees, customers or the public. [emphasis added]

The internal-only code that Kibkalo allegedly leaked includes the Microsoft Activation Server SDK, which is a core piece of Microsoft’s anti-piracy infrastructure. In the FBI affidavit, Microsoft admits that “the potential for harm from misuse of the SDK is generally considered low,” but the risk is that someone could use the code to reverse-engineer a reliable generator of valid product keys for Windows and Office. That prospect is guaranteed to give Microsoft executives major heartburn.

It's worth noting here that this whole incident happened in Summer 2012, before Ed Snowden upended all the pieces on the online privacy game board. In response to a request for comment on this story, a Microsoft spokesperson initially nprovided the following statement:

During an investigation of an employee we discovered evidence that the employee was providing stolen IP, including code relating to our activation process, to a third party. In order to protect our customers and the security and integrity of our products, we conducted an investigation over many months with law enforcement agencies in multiple countries. This included the issuance of a court order for the search of a home relating to evidence of the criminal acts involved. The investigation repeatedly identified clear evidence that the third party involved intended to sell Microsoft IP and had done so in the past.

As part of the investigation, we took the step of a limited review of this third party's Microsoft operated accounts. While Microsoft's terms of service make clear our permission for this type of review, this happens only in the most exceptional circumstances. We apply a rigorous process before reviewing such content. In this case, there was a thorough review by a legal team separate from the investigating team and strong evidence of a criminal act that met a standard comparable to that required to obtain a legal order to search other sites. In fact, as noted above, such a court order was issued in other aspects of the investigation.

Featured

One interesting detail in Microsoft's statement is not included in the FBI Special Agent Ramirez's affidavit. According to Microsoft, there was "clear evidence that the third party involved intended to sell Microsoft IP and had done so in the past." That suggests the possibility that more charges will be filed, perhaps in France.

The FBI affidavit and Microsoft's statement only tell one side of the story, of course. Kibkalo will get the opportunity to present his defense soon. Meanwhile, the facts were compelling enough that the United States Attorney asked a Federal magistrate to detain Kibkalo pending trial because of the “serious risk the defendant will flee,” presumably to his native Russia.

In a further update, Microsoft says it will tighten its procedures going forward:

John Frank, Vice President & Deputy General Counsel:

We believe that Outlook and Hotmail email are and should be private. Today there has been coverage about a particular case. While we took extraordinary actions in this case based on the specific circumstances and our concerns about product integrity that would impact our customers, we want to provide additional context regarding how we approach these issues generally and how we are evolving our policies.

Courts do not issue orders authorizing someone to search themselves, since obviously no such order is needed. So even when we believe we have probable cause, it’s not feasible to ask a court to order us to search ourselves. However, even we should not conduct a search of our own email and other customer services unless the circumstances would justify a court order, if one were available. In order to build on our current practices and provide assurances for the future, we will follow the following policies going forward:

- To ensure we comply with the standards applicable to obtaining a court order, we will rely in the first instance on a legal team separate from the internal investigating team to assess the evidence. We will move forward only if that team concludes there is evidence of a crime that would be sufficient to justify a court order, if one were applicable. As an additional step, as we go forward, we will then submit this evidence to an outside attorney who is a former federal judge. We will conduct such a search only if this former judge similarly concludes that there is evidence sufficient for a court order.

- Even when such a search takes place, it is important that it be confined to the matter under investigation and not search for other information. We therefore will continue to ensure that the search itself is conducted in a proper manner, with supervision by counsel for this purpose.

- Finally, we believe it is appropriate to ensure transparency of these types of searches, just as it is for searches that are conducted in response to governmental or court orders. We therefore will publish as part of our bi-annual transparency report the data on the number of these searches that have been conducted and the number of customer accounts that have been affected.

The only exception to these steps will be for internal investigations of Microsoft employees who we find in the course of a company investigation are using their personal accounts for Microsoft business. And in these cases, the review will be confined to the subject matter of the investigation.

The privacy of our customers is incredibly important to us, and while we believe our actions in this particular case were appropriate given the specific circumstances, we want to be clear about how we will handle similar situations going forward. That is why we are building on our current practices and adding to them to further strengthen our processes and increase transparency.

TIMELINE

The following timeline of events in this case is taken from documents filed with the United States District Court in Seattle, Washington:

July 31, 2012: Kibkalo uses an email account associated with his Windows Live Messenger account to communicate with his contact in France, sending SkyDrive links to six zip files of prerelease hotfixes for Windows RT.

August 1, 2012: Kibkalo requests access to Microsoft's Out-Of-Band [OOB] server. Access is granted on August 2.

August 18, 2012: Kibkalo accesses the OOB server and transfers code to a virtual machine on a server in Redmond. He subsequently places one compressed file (PIDGENXSDK.RAR) on his personal SkyDrive account and then uses MSN Messenger to provide the blogger with links to files on his SkyDrive account and encourages him to share the SDK with others to write "fake activation server" code.

September 3, 2012: Outside source contacts Steven Sinofsky, indicates he had been contacted by blogger who sent proprietary code.

September 7, 2012: After what it describes as "a thorough review by a legal team separate from the investigating team and strong evidence of a criminal act that met a standard comparable to that required to obtain a legal order to search other sites," Microsoft's Office of Legal Compliance (OLC) approves "content pulls of the blogger's Hotmail account."

September 9, 2012: Via IM, Kibkalo and the French blogger discuss the logistics of exchanging data.

September 24, 2012: Microsoft investigators interview Kibkalo over the course of two days; those investigators tell the FBI Kibkalo admitted to stealing a large number of products. Investigators also say they found evidence that he had given the blogger access to servers on Microsoft's corporate network.

July 2013: Microsoft investigators share the results of their internal investigation with the FBI.

March 17, 2014: On the basis of an affidavit submitted by the FBI, United States Magistrate Judge Mary Alice Theiler "finds that there is probable cause to believe the Defendant [Kibkalo] committed the offense set forth in the Complaint."