On Wall Street, the time value of money has been redefined. It does not include you

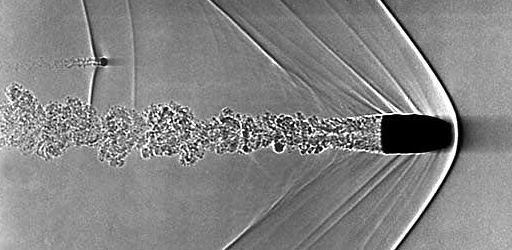

An electric signal takes a nanosecond to travel a foot, essentially.

These days, that distance matters. At least on Wall Street.

If you want to discover prices on stocks first – and act on them first – you have to get them first. Which means sweeping the market at speeds measured in the millionths of seconds. Every little hardware and software advantage you can think of matters. So does the distance that an electric signal travels, even if it is lightspeed.

Which is why you may want to take note of the data center that the New York Stock Exchange is setting up next year across the Hudson River in New Jersey.

If you’re running a competing electronic exchange or trying to make money on sizable chunks of “dark” investment capital that likes to remain unseen to the public at large, you are going to look seriously at sitting under the same roof as your ostensible competitor.

Why?

Because the nanoseconds (billionths of a second), microseconds (millionths) and milliseconds add up, otherwise. If your data center is, alas, on Wall Street, it might be a full three miles to get across the river to the NYSE’s data center. And three miles back.

Translate that into feet and it’ll take an electric signal – a piece of data – 32 millionths of a second to get there and back.

Those are 32 millionths of a second that you won’t squander, if you sit under the same roof. Your exchange and orders placed through your system will connect directly to the NYSE’s own operations. And the operations of any other exchange under that roof.

"We think of this as a game-changer for us,’’ Murray White, NYSE Technologies' senior vice president, said in Securities Industry News.

What’s worrisome about a “single co-location environment” is that this will aid and abet Wall Street’s own implementation of Moore’s law.

Right now, it’ll be a big deal to have your exchange’s servers sitting next to that other exchange’s servers so that you save the 15,840 feet that your signals otherwise would have had to travel to get across the Hudson and back. Tomorrow, you’ll be fighting over where your servers are located within the co-location facility – so that your signals don’t have to travel 200 yards and back, if a competitor’s are traveling just 50 feet and back.

You’ll be trying to figure out how to put as much software back into hardware circuitry, to eliminate delay in crunching instructions. You’ll figure out how to route each piece of data in a message as fast as you can, in as direct a route as you can, to save more millionths of a second. So you can spot market opportunities, react and act, before any other high-speed traders do. And certainly the public investor, who still thinks “real-time” data means up-to-the-second information.

The problem here is there’s no semblance of a fair fight, any more. Time is money. And time is getting sliced way too thinly, thanks to increasingly aggressive trading programs. With high-frequency traders running the field with thousands of orders a second – each – everyday investors pretty much have to figure that they can’t really compete.

They pretty much have to buy, hold and pray that they catch broad movement in a stock correctly.

Because they can’t begin to profit – or compete -- on the microsecond movement.

Unless they plan to rent space at the NYSE’s new co-location facility. And perhaps eat and sleep there, as well.