Dell turns 40: How a teenager transformed $1,000 worth of PC parts into a tech giant

For the personal computer industry, 1984 was a wild ride, dominated by a handful of startups run by young people with big ideas.

The year began with a bang when 28-year-old Steve Jobs introduced the Apple Macintosh with the iconic "1984" Super Bowl ad directed by Ridley Scott. That ad was an audacious shot at IBM, which had enjoyed wild success after introducing the first Intel-based personal computer three years earlier.

Also: The Mac turns 40: How Apple's rebel PC almost failed again and again

Meanwhile, 28-year-old Bill Gates was leading Microsoft's development of MS-DOS, the operating system that would power a generation of IBM PC clones; a year earlier, Microsoft had released Windows version 1.0.

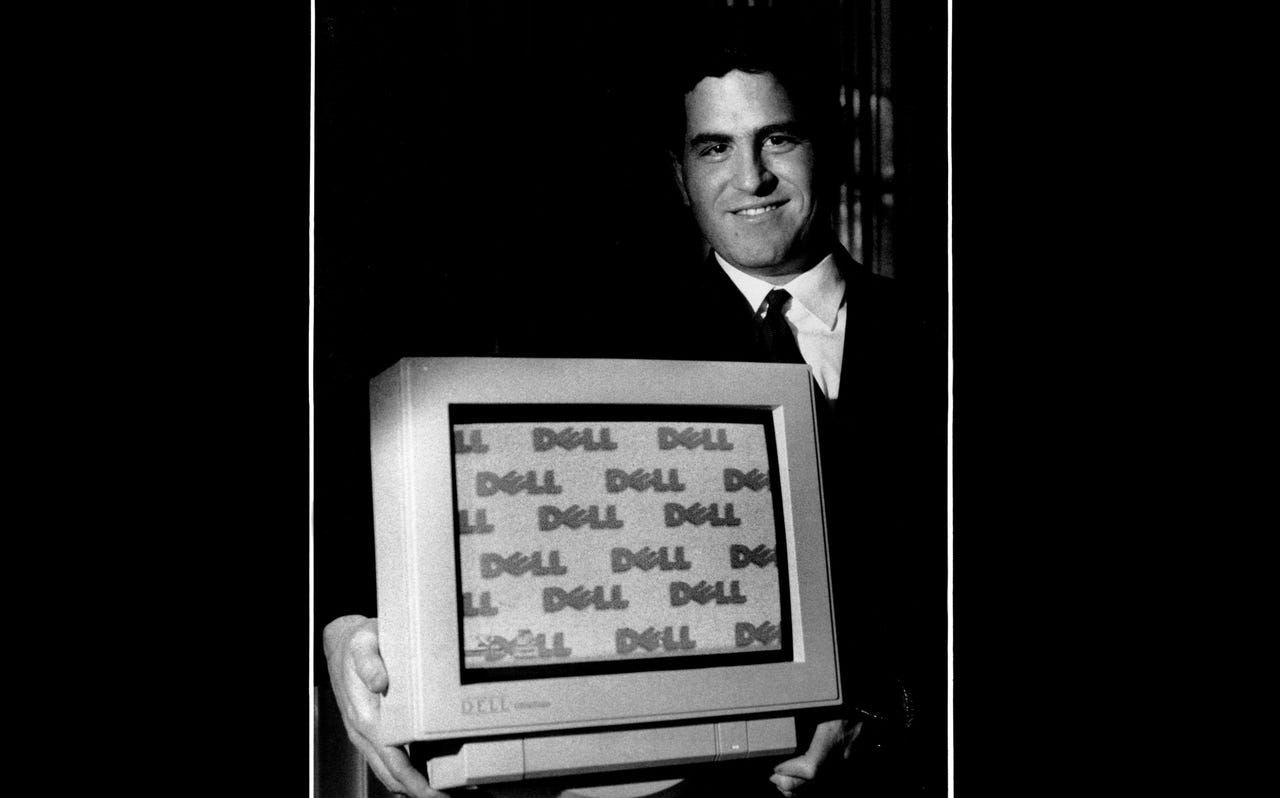

But those two young CEOs were downright ancient compared to Michael Dell, a 19-year-old freshman at the University of Texas. Dell started a small business at the beginning of 1984, buying $1,000 worth of PC parts and taking orders over the phone to upgrade IBM PCs. By the end of the year, the company was building custom PCs that could match the performance of an IBM-branded PC at half the price.

Dell's company was incorporated 40 years ago this month as Dell Computer Corporation, doing business as PC's Limited. Its evolution provides a fascinating roadmap of the history of the personal computer.

Also: It's baaack! Microsoft and IBM open source MS-DOS 4.0

In those early months, Michael Dell wrote later, the company's manufacturing staff consisted of "three guys with screwdrivers sitting at six-foot tables upgrading machines." Within a year, the company had moved into a 30,000-square-foot building and was on its way to $60 million in annual sales. Four years later, on June 22, 1988, the company dropped the PC's Limited brand and went public with a market capitalization of $85 million. Dell's stock hit a peak market cap of $100 billion in 2000, when the collapse of the dot-com bubble finally brought the industry back to earth.

The early years

The secret of Dell's success was its business model, which sold built-to-order PCs direct to consumers and businesses. That strategy eliminated the costs of maintaining inventory and the risk of building products that customers didn't want, like the IBM PCjr, which was launched in 1984 and discontinued a year later. (Microsoft experienced a similarly disastrous product launch nearly 30 years later with its original Surface tablet.)

Forty years later, we take the dominance of that Intel-based PC model for granted, but in 1984 it was anything but a guaranteed path to riches. Among hobbyists, there were plenty of alternatives, including the brand-new Macintosh, the Atari ST, Radio Shack's TRS-80, and the Commodore Amiga (introduced in 1985).

But thanks to popular business apps like Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect and a hardware design that allowed for easy expansion with add-in cards, the IBM-compatible PC market took off. From the start, Dell was consistently at or near the top of the list of alternatives to IBM. The introduction of Windows 3.1 in 1992, followed three years later by Windows 95, continued the seemingly unstoppable growth of the PC market.

Also: At 35, the web is broken, but its inventor hasn't given up hope of fixing it yet

Within the first 15 years after its humble beginnings, Dell's business grew at a staggering pace. In 1990, the company opened a manufacturing plant in Limerick, Ireland, to fulfill orders from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, and in 1995 it expanded its business to Asia and Japan.

By 1992, only four years after its stock began trading, the company had made the Fortune 500. Between 1996 and 2000, Dell's daily sales grew from $1 million to $40 million a day, and its stock price nearly doubled every year. By 2000 it was the number-one PC maker in the US and second only to Compaq worldwide.

Dell versus Jobs

Besides becoming fabulously wealthy starting public companies, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Michael Dell had something else in common. All three had dropped out of college to build their businesses.

Also: Humanizing technology: The 100-year legacy of Steve Jobs

While Gates and Dell were presiding over fast-growing companies in the 1980s, Steve Jobs was pursuing a very different career path. In 1983, Jobs had recruited John Sculley from PepsiCo to be Apple's CEO. ("Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?" Jobs famously asked.) Two years later, Sculley fired Jobs, and Apple descended into a downward spiral that would result in Sculley himself being fired by Apple's board a few years later and earning him a spot on CEO Magazine's list of history's worst CEOs.

In 1997, with Apple flailing as a public company, Michael Dell was asked what he would do as CEO of Apple. "What would I do?" he reportedly answered. "I'd shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders."

That answer didn't exactly age well, and Dell tried to walk it back in a 2011 interview in which he claimed his answer was misconstrued.

Today, Apple has a market capitalization more than 30 times larger than Dell's.

The 2000s: Consolidation and "Dell Hell"

Throughout the 1990s, Dell had significant competition in the direct-sales PC space. Today, most of those competitors are gone. The biggest of the bunch was Gateway 2000 (which later dropped the 2000 from its name). The company had copied Dell's business model, with an emphasis on its Midwestern roots (Iowa and then South Dakota). In 1997, the company made more than $1 billion in profit on $6.3 billion in revenue and turned down an acquisition offer from Compaq for $7 billion. By 2007, it was nearly out of business, and the brand was sold to Acer for $700 million.

Also: Canonical turns 20: Shaping the Ubuntu Linux world

The two biggest competitors in those years were Hewlett-Packard and Compaq. The latter introduced the first (barely) portable IBM PC clone in 1983 and was widely regarded as the leading PC maker in terms of advanced technology.

When HP acquired Compaq in 2002, the combined company became, at least on paper, a powerhouse. Meanwhile, Dell was having an absolutely terrible decade. With his company seemingly firing on all cylinders, Michael Dell had stepped down as CEO in 2004 and turned the reins over to Kevin Rollins. Rollins' background was as a management consultant, not a technologist. During his brief tenure as CEO, the company lost its market share lead to HP and was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission for "accounting irregularities." More importantly, the company's reputation for customer service took a major hit as complaints grew.

I know, because I was fielding a tremendous number of complaints about Dell service at that time, and I had experienced multiple support issues in my side hustle as a PC support tech. A-list blogger Jeff Jarvis wrote about his experience, in dozens of posts and coined the phrase "Dell Hell," which went viral.

Also: The best Windows laptops you can buy: Expert tested and reviewed

In November 2004, CNET interviewed Rollins, who asserted that customer service had been "a challenge [but] we think we've got that one now under control." I responded on my personal blog (this was two years before I joined ZDNET), with a post titled "Memo to Dell CEO Kevin Rollins."

Memo to Kevin: No, your customer service problems are not under control. Not even close. Do you have anyone at your company reading blogs like this one? I didn't think so.

If you Googled "Kevin Rollins email address" in 2005 or 2006, that post came up as the top result, and over the next few years the comments section was absolutely filled with complaints from unhappy customers.

And it turned out that someone at Dell was indeed reading blogs about the company's support problems. In early 2007, I was invited, along with a dozen or so other bloggers and some unhappy customers, to a sit-down session with Michael Dell, which I documented here: "My 42 minutes with Michael Dell."

The meeting was the latest in a series of efforts that suggest Dell (the company) really is getting serious about listening to customer complaints. ... It takes a long time to undo the sort of damage that poor support did to Dell's corporate reputation in the past two years. Whether the company can turn "Dell Hell" into "Dell Help" as its chairman insists is still an open question. But so far, it's making all the right moves.

In December 2007, Rollins resigned and Michael Dell returned as CEO.

Going private and then public again

With Michael Dell back as CEO, the company settled in as a steady third place on the list of global PC makers, behind Lenovo, which had bought up IBM's PC business in 2005, and HP.

Over the next five years, the company got serious about the enterprise business, acquiring Perot Services and rebranding it as Dell Services. A Reuters timeline of this period shows just how busy Dell was:

- 2010 - Dell ... goes on an acquisition spree and snaps up companies in storage, systems management, cloud computing and software: Boomi, Exanet, InSite One, KACE, Ocarina Networks, Scalent and Compellent.

- 2011 - Acquires Secure Works, RNA Networks and Force10 Networks, rounding out its enterprise capability.

- 2012 - Makes another half dozen acquisitions including storage protection company Credant Technologies and software manufacturer Quest Software.

In 2013, with the personal computer market slumping, Michael Dell orchestrated a $24.4 billion private equity buyout that made Dell a private company once again. That move allowed the company to get off the treadmill of quarterly results and focus on long-term gains. And three years later they made their biggest acquisition of all, paying $67 billion to acquire EMC and create the world's largest "privately controlled, integrated technology company."

Also: How Ubuntu Linux snuck into high-end Dell laptops (and why it's called 'Project Sputnik')

As ZDNET's editor-in-chief Larry Dignan noted at the time: "With the move, Michael Dell largely transforms his company, which went private to diversify the business away from PCs." The combined company set out to be a leading enterprise player in servers, storage, virtualization (via VMware), converged infrastructure, hybrid cloud, mobile, security (via RSA), and big data (via Pivotal).

All of those acquisitions finally paid off in 2018 when the company, now renamed Dell Technologies, returned to the New York Stock Exchange in a deal that gave the company a market cap of $21.7 billion. Since then, the company's stock has gone up 500%.

Dell today

Remember Ben Curtis? If the name doesn't ring a bell, his tagline certainly will: "Dude, you're getting a Dell."

That smiling stoner was the face of Dell in TV ads that ran in 2000, when the company was still focused primarily on selling PCs. He probably wouldn't recognize the company today. Nor would the 19-year-old freshman who founded Dell 40 years ago.

In its most recent annual report, Dell Technologies reported it has 133,000 employees worldwide. More than 21% of its $101 billion in revenue came from services, and another $9.3 billion came in the form of a special dividend from its spinoff of VMware to Broadcom for $67 billion.

Also: I tested Dell's XPS 13 and its eye-catching design is its second best feature

Dell still sells branded PCs and peripherals, including notebooks, desktops, workstations, displays, and docking stations, with half of its sales generated outside the United States. But the company also sells a wide range of servers, storage, and networking products that help enterprise customers manage and run cloud-based environments, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data analytics. The company also continues to resell VMware services and owns Secureworks, a leading global cybersecurity provider.

Not a bad return at all on an initial investment of $1,000.