Governments to declare war on mathematics and dumb criminals

It is too late for a reasonable person to think the proliferation of end-to-end encryption can be stopped, and yet it appears a collection of Western governments are determined to see how much blood they can get from this particular stone.

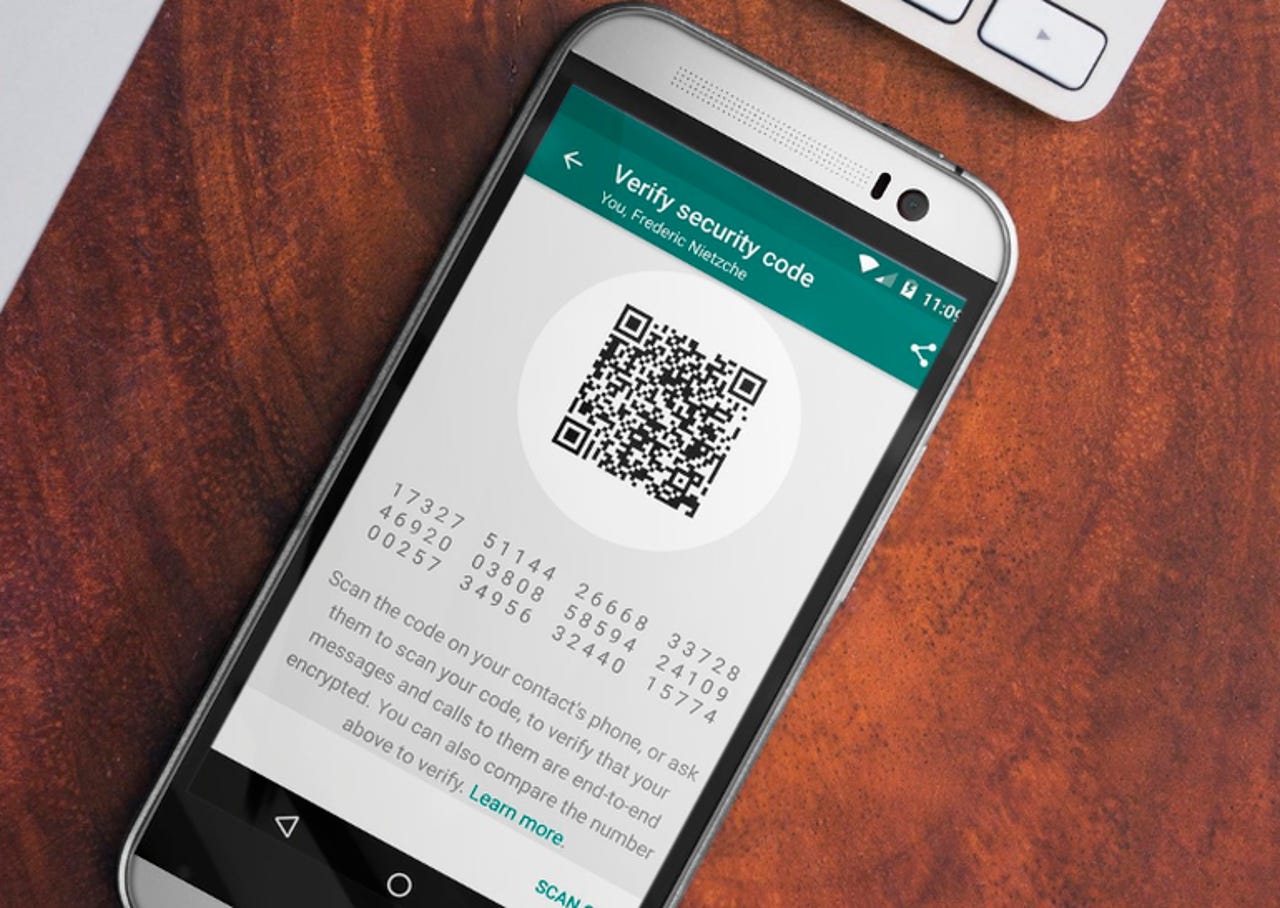

For anyone interested in protecting their communications, a quick Google search will reveal a selection of secure and anonymous services available for use, and a plethora of libraries available if you wanted to create your own application. Regardless of whatever progress governments make from this point, the code is already out there and will continue to be used and built upon.

Yet here we are with the politicians of the United Kingdom and Australia leading the charge to clamp down on the internet. Some days, it seems backdoors are being promoted; other times, those claims are watered down.

The rub comes from the knowledge that any progress made to enforce a clampdown will impact the law-abiding majority of the population in the form of weaker encryption, speed humps, and greater impositions. The only people likely to be caught up by the changes are those too stupid to know about them, in which case one would expect them to be caught by existing measures.

Nevertheless, the politicians will push on in order to appear as though they are doing something, and the relatively regulation-free internet is an easy target.

The linchpin in any future scenario is not any of the governments currently talking about encryption -- it is the United States.

While non-US governments can kick and scream all they like about internet companies thumbing their noses, as most internet giants are based in the US, the overseas governments are kept at arm's length.

Given the current occupiers of the White House and Congress, it's not too hard to imagine a situation where Theresa May could say that any government that refuses to help the UK in its quest to gain communications data are "soft on terror", and, before the US president could complete a tweet storm, the United States government would be leaning on Silicon Valley to the same extent.

The laws of mathematics, and the urge to avoid years of legal challenges, will likely see the quest to completely bust encryption pushed to one side, in favour of something else.

Last week, Germany arrived on the scene with a plan to have messages sent to a store before they are encrypted -- which Apple would likely welcome in a similar fashion to the FBI's demands to decrypt an iPhone.

Even if governments could make tech giants add such features, it is merely part of a never-ending game of whack-a-mole, as any evildoer worth their salt does not use a platform or an operating system that could compromise them.

At the current time, it is possible for authorities to get some idea of what the people they want to monitor on social media are up to -- but should the changes they want be enforced, the targets will retreat into a world of proper encryption where authorities cannot see them.

The BBC highlighted recently that although extremists may start out with online material, it is influence and meeting with people in the real world that moves a person into full extremist mode.

On the other side of the debate, a late entrant into the encryption quagmire is the European Parliament, which may enshrine citizen protection from governments looking to weaken encryption, but the proposal is a draft [PDF] and has a long way to go before being legislated.

While politicians have been running around like headless chickens when discussing encryption, those who interact with internet companies have been more circumspect.

Australian Special Adviser to the Prime Minister on Cybersecurity Alastair MacGibbon said recently that intelligence agencies are more likely to want metadata instead of going for an encryption backdoor.

Conveniently, Australia already imposes a warrantless metadata retention scheme that demands telcos and email providers store two years' worth of customers' call records, location information, IP addresses, billing information, and other data for authorities to access.

The laws did not demand the same of over-the-top providers -- such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Google, Apple, and Twitter -- but it is not hard to imagine a situation where America is pressured to allow the likes of Australia and the United Kingdom to vacuum up the data of local users, or provide near-instant responses to individual metadata enquiries from Western governments.

Although it is currently conjecture which way the Western governments move on encryption, this much is true: The masterminds they purport to be after will not be there, and haven't been there for some time thanks to existing end-to-end encryption.

ZDNet's Monday Morning Opener

The Monday Morning Opener is our opening salvo for the week in tech. Since we run a global site, this editorial publishes on Monday at 8:00am AEST in Sydney, Australia, which is 6:00pm Eastern Time on Sunday in the US. It is written by a member of ZDNet's global editorial board, which is comprised of our lead editors across Asia, Australia, Europe, and the US.

Previously on Monday Morning Opener:

- 3 things you need to know about cybersecurity in an IoT and mobile world

- WWDC 2017: Apple's to-do list needs to include a dose of AI

- Governments stand ready to regulate a cyberscape they do not understand

- Ransomware and the age of insecurity

- Omnichannel debunked in less than 5 minutes

- 3 things to know about the cloud v. data center decision

- A VPN will not save you from government surveillance

- The death of the smartphone is closer than you think. Here's what comes next

- What do PCs, Samsung's Galaxy 8 and Toyota's concept vehicle have in common? Notable design

- Convergence returns as former players exit