Bringing Colossus back to life

The Colossus codecracking computer has recently been kicked into action for the first time in more than 60 years.

Colossus is widely recognised as one of the world's first digital computers. It is kept in its original location at Bletchley Park, where it cracked Nazi codes during World War II and played a key role in the Allied victory.

It was one of the first-ever programmable computers, featured more than 2,000 valves, and was the size of a small lorry.

It has recently been used to crack new messages enciphered using the same system employed by the German high command during World War II.

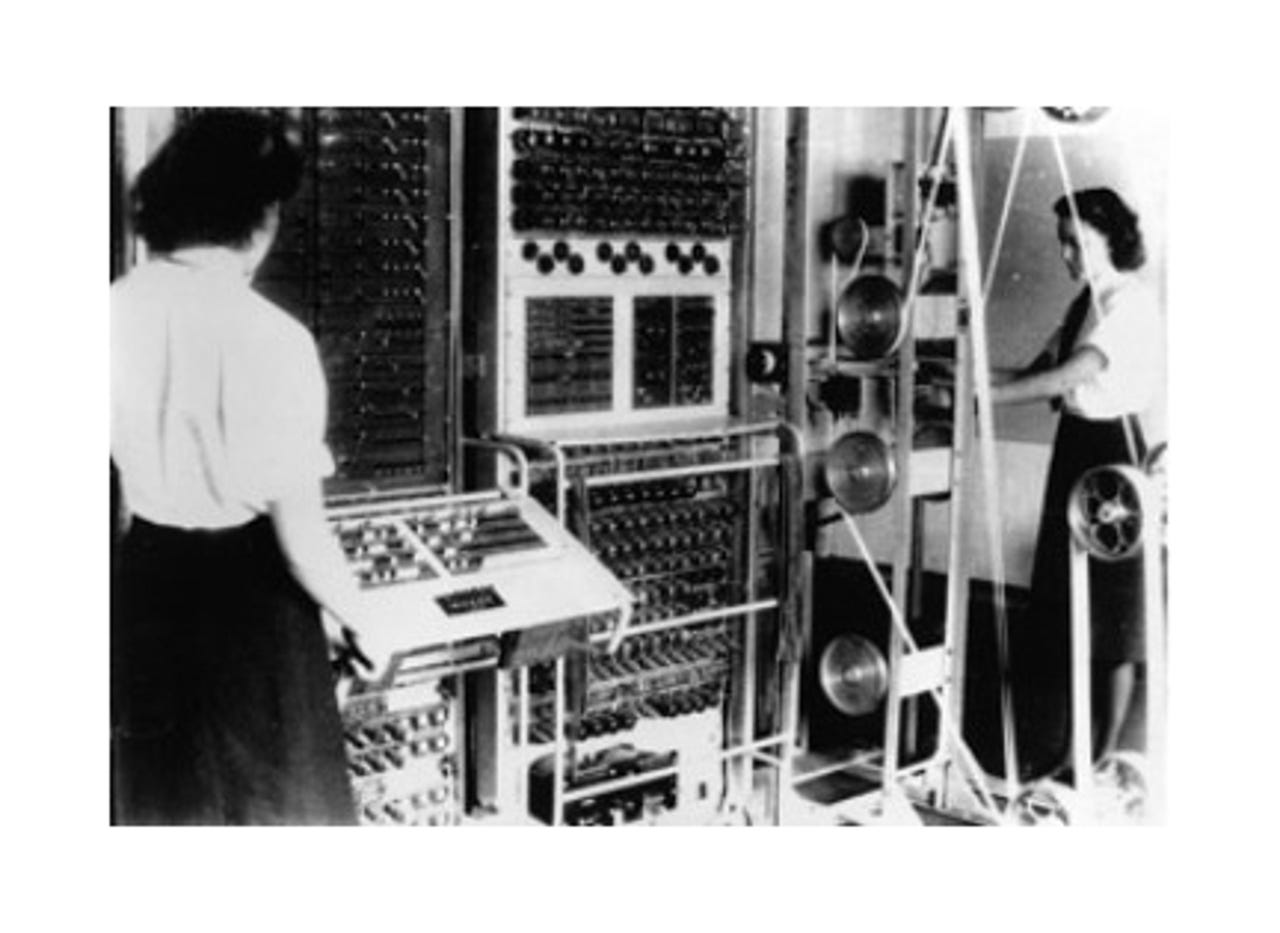

Pictured are Wrens using a Colossus Mark II computer in the 1940s.

The rebuilt Colossus was last week put to work on intercepted radio messages transmitted by radio amateurs in Paderborn, Germany, which had been scrambled by a machine used by the German high command in wartime.

Pictured is the reconstructed machine, which took 6,000 volunteered man days to rebuild.

Pictured with the revamped machine is Tony Sale, who led the 14-year Colossus rebuild project.

Colossus was originally designed by a group at Bletchley Park which included engineer Tommy Flowers and mathematician Max Newman.

The prototype, Colossus Mark I, arrived at Bletchley in December 1943 and was operational by February 1944.

An improved Colossus Mark II was first installed in June 1944 and was working in time for Eisenhower and Montgomery to be sure Hitler had swallowed the deception campaigns prior to the D-Day landings on 6 June, 1944.

There were eventually 10 working Colossi at Bletchley.

Colossus was the first machine to break the Lorenz — a complex cipher machine used to pass important messages between the German army field marshals and their central high command in Berlin.

Lorenz had to be cracked by carrying out complex statistical analyses on the intercepted messages. Colossus could read paper tape at 5,000 characters per second and the paper tape in its wheels travelled at 30 miles per hour.

This meant the huge amount of mathematical work that needed to be done could be carried out in hours, rather than weeks.

Pictured are Nigel Shadbolt, the former president of the British Computer Society (BCS), and Andy Clarke, one of the founders of the Trust for the National Museum of Computing.

The BCS donated £75,000 to keep and develop Colossus in its original location.