BioServe Space Technologies: The magic behind shuttle experiments

BioServe Space Technologies, a center within the University of Colorado Boulder, specializes in conducting microgravity life science research and designs and develops space flight hardware. It currently has two piece of its hardware on the International Space Station and two on the Space Shuttle mission.

BioServe Space Technologies, a center within the University of Colorado Boulder, specializes in conducting microgravity life science research and designs and develops space flight hardware. It currently has two piece of its hardware on the International Space Station and two on the Space Shuttle mission.

Yesterday I spoke with Stefanie Countryman, the center’s director of business development and director of its K-12 science education payloads. A former speech language pathologist, Countryman has worked at the center for more than a decade. We talked about mice and spiders in space and why she wouldn’t be a good candidate for space flight.

Say there’s a researcher who wanted to conduct an experiment in space. Where do you come in?

Our center works with researchers via several different avenues. It could be a NASA-sponsored scientist, and then they’d decide what hardware they need and they’d use us as the payload developer. We support quite a few NASA-sponsored scientists. We also partner with commercial companies to fly certain science experiments. We’ve worked with Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, usually biotech or pharmaceutical companies. We’ve also worked with companies in the forestry industry.

What were they studying?

This was a while ago, but we had a consortium of companies that were flying a loblolly pine tree, which is used in paper-making. When companies make paper they have to remove this structure from the tree called lignin, which gives the tree its strength. So if you can fly a tree in space, the lignin is like the bones in your body--your bones don’t need to support your structure in space. So the seedlings don’t lay down as much lignin. And if you could figure out a way to do that on Earth, where the companies wouldn’t have to go through the process of removing the lignin, that would make the industry less energy and pollution-intensive.

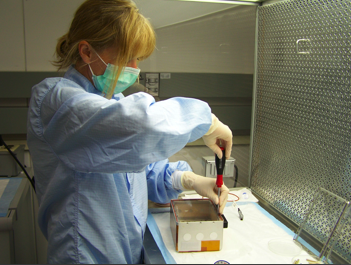

Tell me about some of the hardware you’ve developed to put the experiments on a spacecraft.

Our workhorse hardware is like a smart incubator, called a CGBA (commercial generic bioprocessing apparatus). We have two on the International Space Station and two units on the shuttle, each about the size of a mid-deck locker. Each holds a volume of 27 liters. It’s like a big empty box, and we can change the temperature. Then we have smaller pieces of hardware that fit inside, and that’s what actually holds the life science experiments, while the CGBA provides the appropriate environment.

In our office, we have a payload operations and command center. So when our payloads are up and running on the Space Station, we can communicate directly, we can see the temperature, and we can change it.

Your office must be a little hectic right now.

We’re very busy now. We had 5 payloads on this mission, which is a lot. Normally there are two, maybe three.

- One is yeast-related;

- There is an Amgen bone-loss experiment with a mouse;

- There is a microbe experiment;

- One is looking at virulents of salmonella to develop a salmonella vaccine;

- And one looks at the jatropha plant, which is important in the development of biofuel, looking at how you could grow this plant in areas that are not usually hospitable for agricultural plants, so you’re not taking away land that would be used for crops.

What does the end of the Space Shuttle era mean for you guys?

Honestly, our center has a long history of fling on the shuttle. STS-135 was our 39th shuttle mission. We’re part of the University of Colorado, and we train mostly masters students. On one hand, with the shuttle program ending, it definitely impacts how we educate our students.

Our students who come through the center are highly sought after by corporations and NASA because they get hands-on experience in developing the hardware, see the scientists load the science into the hardware, are able to be part of the operations when it’s on the station and hand it back to the scientists after the mission. They get the whole process of flying experiments in space.

So for a time now, we’re not going to be able to provide that education for our students. We have projects we’re working on, but it won’t be quite the hands-on they’ve had for the last 20 years. There are other space programs-- Japanese, European and Russian vehicles and the commercial vehicles that hopefully will come online in 2012 . We’ll have to develop hardware that will support these other vehicles, and we’ll have to learn the other systems. We know the NASA paperwork and the flying systems but we don’t know that, for instance, with the Japanese .

So it impacts our center, and it’s really a sad day.

Is it possible—for experimental purposes—to create microgravity on Earth?

You can’t ever remove gravity on Earth. They have centrifuges, which have increased gravity. And there’s the clinostat, or bioreactor—a rotating wall bioreactor. But you really can’t make a microgravity chamber on Earth.

Tell me about the spider in space for your K-12 program.

There are two spiders up there –golden orb weavers, native to southern parts of the United States. They’re on the Space Station, coming back on the 135 shuttle. They were originally supposed to live their life on the station but now they’ve been up there for 60 days.

The went up as juveniles so they grew up in space. We’re hoping they’ll still be alive when they come back. The food supply was designed to last 30 to 45 days, and they were living on fruit flies, but now they’re on their own living without too much food. They can live a long time without food, so we’re hoping to get them back and get them hydrated and look at them under the microscope.

The experiment was to look at how they would spin their webs in space They spin these half orbs that have a three-dimensional aspect. In space they spun circular webs, which are very different. On the ground, they sit on the top of the web looking down. In space they sat in the middle of their web and faced all different ways. You can see YouTube videos here and here.

If you had an opportunity to travel in space, what experiment would you conduct?

I get sick on roller coasters, so I’m probably not the best person to ask. I guess I would just like to see the life science experiments in space continue. Now that the shuttle is retired, it’s hard for the life sciences. The model is that we send our experiments to space and then bring those samples back and then analyze them on the ground. Without the shuttle we don’t have that capability anymore.

There is some hardware being developed to do some analysis in space while on the station, but it’s a difficult thing to do. So I would hope we’re able to continue to do that and that the vehicles that can eventually bring home samples get online pretty quickly.

We built this big space station, and it was supposed to be a science platform, and I’d really like to see it used as a science platform.

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com