Home Computers: 100 Icons that Defined a Digital Generation, book review

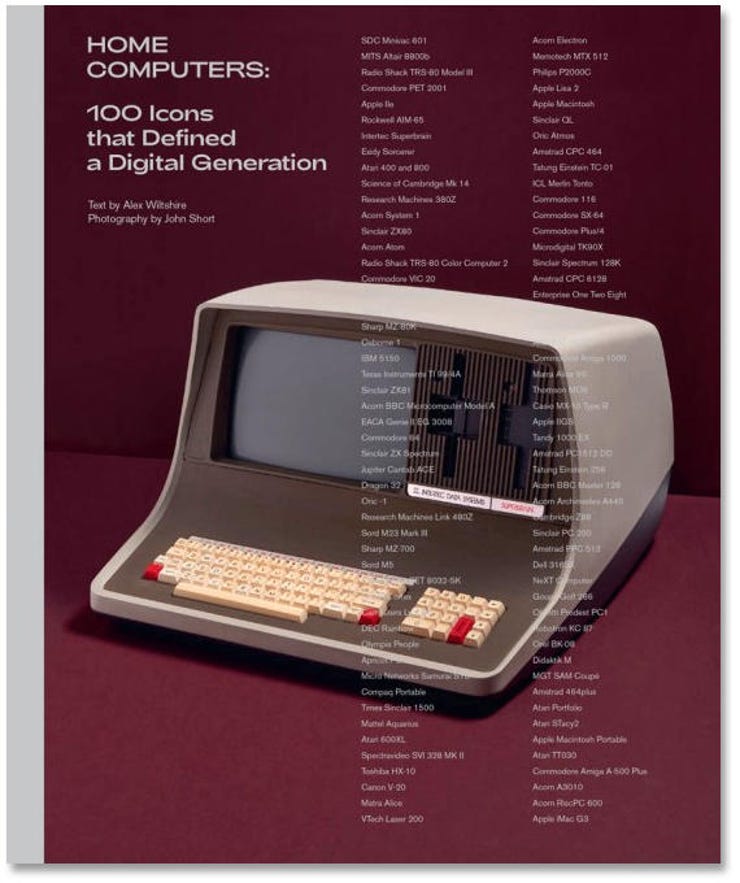

Home Computers: 100 Icons that Defined a Digital Generation • By Alex Wiltshire • Thames & Hudson • 256 pages • ISBN 978 0 500 022160 • £24.95

It's unnerving to be consigned to history. Home Computers: 100 Icons that Defined a Digital Generation by Alex Wiltshire puts your reviewer firmly in that box. Of the 100 computers glossily photographed by John Short, I've owned about fifteen, used about fifty, and was on the design team for one. At the time, every computer in these pages was cutting-edge in some way – an exciting stab at predicting, or even defining, the future. Now they're gone, like bytes in the RAM.

This book will be a very different experience for different readers, depending on when, or whether, their own experience of home computing enters its timeline. Home Computers focuses on the glory years of innovation, hope and failure between the 1970s and the 1990s (or, in Intel time, from 8080 to 80386), pulling in a wide variety of the famous and obscure. Publisher Thames and Hudson knows how to lay on a pictorial feast, and the pictures are the book's greatest strength. Drawn from the collection of the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge, these are gallery-quality pictures of museum-quality artefacts.

The book is somewhat less confident in its text. There is uneven copy editing: "At £39.95, the MK14 was cheaper than any other computer on the UK market". So it was, but four pages later we read that: "At £79.95 for a kit and £99.95 for a pre-assembled model, at launch the ZX80 was the cheapest computer ever released in the UK".

The pictures are beautifully shot and capture the visual aesthetic of the home computer revolution – up to a point. Like previous home computer hardware art books, such as Gordon Laing's 2004 Digital Retro, these are the computer as sculpture: statues unearthed from ancient times whose modern context is the museum, the gallery – and yes, the art book.

But those of us who lived through that revolution do not think of these boxes as boxes. They were alive, each with its own quirks of sound and vision, each with its own tactile feel of keyboard and case. They whirred and clunked and buzzed, they picked like fussy eaters at cassette tape software, they were blurry monochrome on the family's second portable TV, or astoundingly vivid technicolor on a monitor, glowing rainbows like you'd never seen before.

And the software – home computers ran software, that was their soul, their life. You wouldn't know it to look at this book, and perhaps that's because it can be read as a book of the museum, the gallery, the context of dead antiquity. There is salvation: YouTube has the restorers running programs, prying and reviving, glorying in these systems as living things. The best use of this book is as a sightseeing guide, a festival programme, that lists and describes places to experience, or live acts to go and see perform. Its concentration on the static makes most sense this way, its lack of liveliness no loss.

Less excusable is the book's fleeting engagement with the actual technologies. No circuit boards, no real treatment of the advances in components that fuelled the revolution. What was going on under the hood not only explains and defines what was actually happening, but it has its own aesthetic – harder to grasp, perhaps, but even more worthy of study as a result. That's absent.

Devil in the detail

Sinclair ZX Spectrum 128: no internal speaker.

But technology in general is not this book's strong suit. Although often broadly right, the details don't always reflect reality. To take just one theme – the Sinclair Research computers. Of the uber-iconic ZX81, the book says it could be expanded up to 64K RAM. That's the address space of the Z80 processor, sure, but in no way matches how the system actually worked. Sinclair only offered a 16K RAM pack – notorious for its wobbly connection – and while the third-party aftermarket offered bigger, anything more than 32K needed considerable ingenuity, which brushed past the 64K limit anyway. And the ZX81's masterstroke, the Ferranti ULA chip, is given a bare mention as a neat cost-cutting exercise. It was instead the first ULA in a consumer product, and set the scene for a huge growth in the market for digital products.

The entry for the ZX Spectrum is equally puzzling, seeming to claim that the hardware designer Richard Altwasser wrote the ROM, which actually came from Steve Vickers at Nine Tiles, while the keyboard doesn't have 'four or five' moving parts. And the ZX Spectrum 128 did not, as the book says, abandon the Spectrum's beeper for a real speaker: the Spectrum's 'beeper' was a real speaker, albeit tiny, while the 128 had no speaker at all, using instead the UHF modulator to play sounds through the TV set. And so on.

There's no point in listing all the tech lacunae in the book – just don't use it as a reference work. Moving swiftly on from the engineering, the book successfully reprises a lot of the standard myths of the period: the Sinclair/Acorn epic spat, Jack Tramiel's adventures at Atari and Commodore, Apple's ups and downs, and many of the other stories that delighted and mystified us all as the brave new world fitfully unfolded.

SEE: How to optimize the smart office (ZDNet special report) | Download the report as a PDF (TechRepublic)

The choice of machines is pretty good, with a decent smattering of exotica alongside a strong showing of the mainstream. Of course there are quibbles. No Radio Shack TRS-80 Model 100, the first mass-market truly portable computer and the last product Bill Gates wrote code for? Is the Hewlett-Packard HP-85, sold exclusively to HP's market of industrial engineering companies, really a home computer? Bonus points for examples of the vast army of Eastern Bloc Spectrum clones, but points deducted for ignoring the Amstrad Spectrums.

Anyone who devoured the pages of 1980s computer magazines, lusting after each and every beast in the menagerie, will find much here to revive the appetite. And just like then, the best advice is to enjoy the pictures and seek out the real-life experience. Just don't believe every word you read.

Iconic: the 1984 Apple Macintosh 128K.

RECENT AND RELATED CONTENT

The tech that changed us: 50 years of breakthroughs

Technology that changed us: The 1970s, from Pong to Apollo

Technology that changed us: The 1980s, from MS-DOS to the first GPS satellite

Technology that changed us: The 1990s, from WorldWideWeb to Google

Technology that changed us: The 2000s, from iPhone to Twitter

Technology that changed us: The 2010s, from Amazon Echo to Pokémon Go

Microsoft's Bill Gates: Steve Jobs cast spells on everyone but he didn't fool me

Read more book reviews

- The Costs of Connection, book review: A wider view of surveillance capitalism

- Speech Police, book review: How to regain a democratic paradise lost

- Nano Comes to Life, book review: Small steps towards a giant leap

- Defending democracy in a post-truth world filled with AI, VR and deepfakes

- Holiday reading roundup: Five books to inform, educate and entertain