Cerebras did not spend one minute working on MLPerf, says CEO

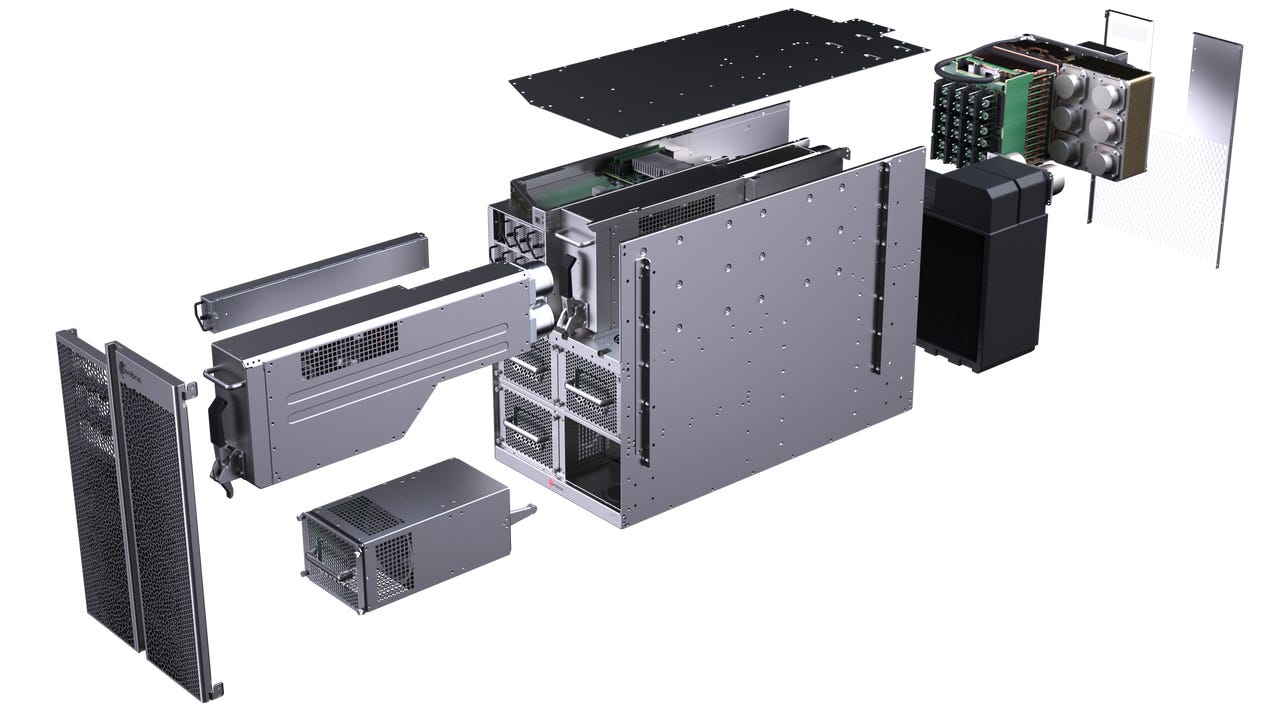

An "exploded" view of the CS-1, with the machined doors at the lower left, pumps for water cooling and fans in the middle, and the "engine block" in the upper right that contains the WSE chip.

Primers

"I'm much less interested in things you can argue about on Twitter and more interested in having real customers come and check out what we have."

That's how Andrew Feldman, chief executive of computer startup Cerebras Systems, describes his view of industry benchmarks for artificial intelligence, in particular, MLPerf, the most widely cited measure of computer chip performance on AI.

Also: Cerebras CEO talks about the big implications for machine learning in company's big chip

"We did not spend one minute working on MLPerf, we spent time working on real customers," said Feldman in an interview by phone.

"We focused time and attention on displacing competitors at large customers, and working to achieve extraordinary performance on customer workloads."

The occasion for Feldman's remarks was the unveiling Tuesday, at the supercomputer show SC19, in Boulder, Colo., of Cerebras's first computer system, the CS-1.

A heat map of the parts of the neural network as they are running on the WSE chip. Each rectangle is a layer of the neural network. The size of the rectangle is how many of the WSE chip's 400,000 cores the layer is using. The aspect ratio of the rectangles is the ratio of compute to communications the layer is using. The hue of the rectangle is its utilization of the chip, with darker being better, meaning, more fully utilized.

The CS-1, a chassis measuring 15 standard rack units high (a little over two feet, and a foot and a half wide and three feet deep), houses the company's WSE chip, unveiled in August, the world's biggest computer chip. A complex system of water and air cooling is engineered into the CS-1, along with a graph compiler software suite that optimizes neural nets to take advantage of the system's enormous power.

Feldman's attitude about MLPerf is a bit heretical. After all, every chip company that promises to unseat Nvidia in neural network training touts its performance on MLPerf. Founded a year ago in February by Google, Baidu and academics, the MLPerf project is meant to be a "fair and useful" measure of how well various neural nets can be trained to accuracy and how well they can perform inference.

Feldman indicated a couple of reasons for eschewing the MLPerf bake-off. One is that MLPerf may be more a measure of how well companies prepare for the test than a true indicator of getting real work done. His remarks imply that the benchmark can be gamed, so the MLPerf results may not be as significant as the effort would imply.

Also: Cerebras has at least a three-year lead on competition with its giant AI chip, says top investor

The "engine block" of the CS-1. The copper part on the left is the "cold plate" that sits behind the WSE chip. The brass block is where cold-water pumps connect.

"MLPerf is a time-to-accuracy number on a very specific network that most people don't use," said Feldman. He wasn't specific, but stats listed by AI startups will tend to emphasize, for example, ResNet-50 training as a common measure, a fairly old neural net at this point.

"Chip-level comparisons never pan out at the system level," added Feldman. "Benchmarks are never actually achieved by your customer."

Hence, "You have to have a system and it has to be compared with customer work."

More important to Feldman was that "we are the first to announce a customer in deployment of any of the startups" working on AI chips, of which there are many. He was referring to the fact Cerebras announced Argonne National Laboratory of the US Department of Energy as its first customer back on Sept. 17. Argonne is talking this week about its use of the CS-1 in things such as cancer-drug research.

Argonne, he pointed out, "had deployed tens of thousands of GPUs, and yet they are consistently choosing us."

In place of MLPerf and such measures, Cerebras offers a variety of comparisons between the CS-1 and other systems, measures it emphasized on Tuesday in its prepared materials.

Also: Cerebras's first customer for giant AI chip is supercomputing hog U.S. Department of Energy

For example, the company says it is three times the performance of Google's TPU 2 Pod, a system that takes up 10 standard racks' worth of equipment. The CS-1 is one 30th that size and draws only one fifth the power of that system, Cerebras claims.

Cerebras also claims its system has more compute power than 1,000 of Nvidia's V100 GPUs while being just one-fortieth the size and one-fiftieth the power. (And, Cerebras argues, it's a lot easier to get a single CS-1 running than it is to tie together 1,000 V100s, an effort that takes months.)

Those may not be industry-standard benchmarks, but they are the measures of success that Feldman believes the world should focus on, measures that may actually sell systems as opposed to granting only bragging rights.